Note: This material was developed for a potential qualitative textbook by Shirley Freed, Ph.D. Please don't copy, quote, publish, or distribute this information. Thanks a lot!

More than a decade ago, I set out to find what success meant for those high school students whose working-class mothers came from the Caribbean to Canada to improve the qualities of their lives. I sought to trace the trajectories of their success.

The traditional methodology B surveys, printed checklists and questionnaires B did not help. My participants complained, AYou are asking the wrong questions. They don=t fit me.@ I had insider knowledge on that perspective. I too had a Caribbean working-class mother and an unfolding pathway to success. What was this knowledge I was seeking and why was I having such difficulty uncovering it? I stopped searching for a while until the nagging questions would not be stilled. I finally realized that my problem was primarily a function of the methodology! I turned to the interview.

After the first round of interviews; however, I began to sense the one-sideness of the questions. I was mining the minds of my participants. They were merely vessels to whom I expected straightforward access. My participants= enthusiasm dwindled, as did my committee=s.

In 1997, I returned to the study at another university armed with an understanding of new methodologies and fortified by a different era and a new committee. I used the open-ended in-depth interview, Aa politically correct dialogue where researcher and researched offer mutual understanding and support@ (Atkinson & Silverman, 1997, p. 305).

I could hear their voices as my participants shared their own stories. Now empowered, they pulled me into a dialogue which was a collaborative production of meaning. Finally, the fit was right. Their words flowed into poetic renditions, artistic portrayals and dramatic presentations. We were capturing their lived experiences and mine too! We loved the process! My researcher self had been found and I was delighted! I no longer needed to mambo to the mathematical constraints of a quantitative study. I could waltz to the words of my participants. (And what a waltz it was, leading to the Selma Greenberg Dissertation Award, presented at the American Educational Research Association meetings in Seattle, WA, April, 2001.)

It is clear that Glenda Mae had specific ideas about knowledge, what counts for knowledge and how it is acquired. She searched until she found a methodology that would allow the experiences of those she studied to be portrayed in an authentic fashion.

In the next section we consider knowledge and notice the impact of life experiences and how they position us in our understanding of what knowledge is and how it is acquired.

In this section we introduce an epistemological model that seeks to retain the strong currents of thought that emerged during and leading up to the Enlightenment. This is not to discount the earlier work of philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle during Ancient times, but simply to try to frame our discussion in modern and postmodern currents.

Reflection: Have you ever felt like this student who said, AHow do I know that I know what I need to know to know what I am expected to know in order to know what I am supposed to know from having participated in this learning environment?@ What does it mean Ato know@ something?

What is knowledge? Most everyone today would say that knowledge is more than just the accumulation of a set of facts. The critical thinking movement has taught us that there is some kind of mental processing needed before information becomes knowledge! Recall from the previous section that the word Ascience@ comes from the root Ascire@ which means Ato know@. One of the results of the scientific revolution and the enlightenment were huge volumes of encycopedias or Abooks of knowledge@.

The study of knowledge in philosophy is called Aepistemology@. What is epistemology? It is not enough to plainly answer that epistemology is the philosophic or the Ascientific@ theory of knowledge, or that it is the knowledge about knowledge. Why did Socrates= statement AI know that I know nothing@ make philosophers think more deeply about epistemology? Why is Aknow thyself@ one of his most important recommendations to psychologists today? Do we really know what we think we know? What can we know, and how do we know it?

AEpistemology@ comes from the Greek words episteme which means knowledge or science and logos that also means knowledge or information. In this section we will be most concerned about sources of knowledge. We will consider these sources as major streams of thought flowing across our landscape. Individual currents or sources may be stronger in your experience than in ours.

Scholars have discussed sources of knowledge in several different ways. Helmstadter (1970) ranks tenacity, intuition, authority, rationalism, empiricism, and science in the order of increasing demands made on the adequacy of the information and the nature of the processing of that information. Reeder (1964) considers authoritarianism, empiricism, rationalism, phenomenalism, intuitionism and the scientific method as the major sources of knowledge. Christenson (2001) suggests that Athere are at least six different approaches to acquiring knowledge. Five of these approachesBtenacity, intuition, authority, rationalism, and empiricismBare considered to be unscientific. . . The sixth and best approach to acquiring knowledge is science, which is a logic of inquiry requiring that a specific method be followed.@ pg. 27. In this section other sources of knowledge are discussed trying to maintain a historical and contemporary context of each source.

Empiricism (Senses)

The first modern statement of empiricism appears in John Locke=s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690). Locke however, was no doubt influenced by Francis Bacon=s (1561-1626) ideas about observation. Bacon advocated that knowledge be built upon observation. While this seems obvious to us today, it wasn=t so obvious to society in the 1500's. People had been educated to believe that knowledge was attained by listening to Church authorities. They were not in the habit of believing that knowledge could be derived from paying attention to their senses in every day experience. And so, Bacon may be called the AFather of Experimental Philosophy@. It wasn=t a huge leap for Locke to pick up ideas of observation and connect them to his ideas about experience. Remember Locke=s Ablank slate@? It was an effective metaphor to capture the notion that all knowledge is derived from experience - in other words, through the senses. But he didn=t stop there! He went on to explain that there must be some introspection about the experiences or in his words Areflection@. (And you thought reflection was a 21st century word!) However, he viewed experiences as the beginning of knowledge. He didn=t reject Descartes (1596 - 1650) rationalism, he was striving for some balance. And so he taught that other factors such as human reasoning helped shape the incoming sensory data to develop hypotheses, propositions and/or conclusions about the world. He believed this reasoning could be inductive or deductive in nature. He also discussed the importance of intuition and language in the formation of understanding. He might be called the AFather of Epistemology@ because of his wide grasp of epistemological issues.

Currently, there are a number of ways of viewing this particular

way of knowing. (Need to explain further). For now, it might be

sufficient to think of Shapiro=s (1981) statement about experience.

AClearly,

if the data of persons= experience are constituted by Aideational

acts@

that inhere in consciousness, as Husserl suugested, rather than

out of sense impressions which originate independently of the

minds that record them (an empiricist view), the locus of evidence

concerning social phenomena of interest to the social scientist

exists somewhere in the interface between consciousness and the

objects of consciousness, that is, between consciousness and that

which persons are conscious of.@ pg. 55.

Contemporary articulations of the importance of Aexperience@ may be found in the literature on Aschema theory@ and Asituated cognition@. Common sense would tell us that sense experiences accumulate over time and continue to influence in some ways all future sensory, introspective experiences B at least to the extent that Areflection@ remains a part of the learning. And this harkens to Kolb=s learning cycle and the Areflective observation@ which he considers critical to our understanding of learning.

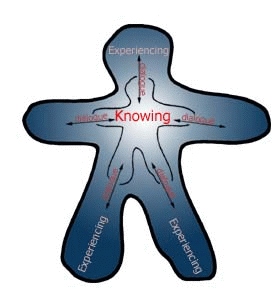

Most researchers and scientists today, would say that empiricism in one form or another continues as a strong current in all discussions about knowledge and sources of knowledge in particular. In an effort to capture the centrality of experience as envisioned by Locke, let=s imagine an individual filled with the experiences of this life. However, the experiences don=t become knowledge without an inner dialogue (reflection).

Reflection: As a researcher, what do you @know@ as a result of your experiences of life? What is to be learned from the experiences of others? How would you capture the essence of their experience? Why would you want to do that? Review Glenda-Mae=s vignette above. What role did experience play in her search for a suitable research method?

Rationalism (Reason)

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) will be remembered for his emphasis on the supremacy of reason and logic. Living in the waning years of the Middle Ages, he seemed compelled to set up a system of thinking that would rely totally on the individual=s ability to reason things out. His classic, Discourse on Method begins with this:

Good sense is, of all things in the world, the most equally shared: for everyone thinks himself so well provided with it that even those who are most difficult to satisfy in every other way, do not usually desire more of it than they already have.

It was a rather poignant way of asserting that the human mind is basically sound and that reasoning would lead to truth! His thinking and writing clearly laid the foundation for the scientific revolution. His view led to an understanding that the mind and body are separated and that the mind is infinitely superior. Reason and mathematical logic became the hallmarks of an emerging science. Have you ever wondered where the words Ahard science@ and Asoft science@ came from? Today, various systems of logic are built on his basic idea that reasonable conclusions can be reached by using deductive syllogisms such as:

All houses in 2000 A.D. in North America have central heating.

Joe=s house is in North America.

Therefore, Joe=s house has central heating.

It=s clear that this kind of reasoning is only as good as the basic premise upon which it is built.

Are we interested in logic and reasoning today? Have you heard anyone say recently, AThat just isn=t logical!@ or ABe reasonable!@ These are small indicators that the stream of rationality begun with Plato, submerged for a while in the Middle Ages and then reoccurring with Decartes is still of value to most people. In fact, contemporary scientists will argue that empiricism and rationalism continue to be the foundations of modern science.

Current brain research, however, suggests that Descartes= separation of mind and body was a huge mistake. In his book entitled, Descartes= Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, Damasio (1994) states that Athe human brain and the rest of the body constitute an indissociable organism, integrated by means of mutually interactive biochemical and neural regulatory circuits (including endocrine, immune, and autonomic neural components) (pg. xvi-xvii). Strong connections between mind and body are portrayed in Goleman=s Emotional Intelligence and in general statements such as, AYou can=t think without feeling nor feel without thinking.@

Authority

The idea that knowledge might come from authorities fell into disrepute towards the end of the Middle Ages simply because of the misuse of power by the church. Yet, today we would hardly deny the need for information that comes from authorities B those specialists who continue to create new knowledge through scientific investigation. A basic tenet of science is that it builds on the knowledge of previous discoveries. A project that doesn=t consider the authorities in the field would not be considered science (Lakatos, 1972). Authority as a source of knowledge gets into trouble when people accept it without thinking about it - rationally or experientially.

Contemporary researchers are expected to find the experts/authorities and be in conversation with them. That is why we do literature reviews. We want folks to know the authorities and be able to extend the knowledge that has been generated up to that point in time.

Intuition

What is Aintuition@? Most would say it is something like listening to your Agut feeling@. It=s fascinating that Locke spoke of intuition as a source of knowledge. He believed that the relationship between ideas was sometimes Aintuited@ - or suddenly arrived at. Remeber Kuhn=s (1960) idea of scientific revolutions! The biggest problem with intuition is that it is difficult to capture with words. Some contemporary epistemologists suggest that things of the Aspirit@ should be thought of as intuition. Graziano and Raulin (2000) discuss knowledge received directly from God as a component of Aintuition@. We have chosen to put them in a separate category in an effort to remain true to their historical context.

Contemporary thinkers (Klein, 2000) have shown that intuition

is the result of many life experiences. Because human beings constantly

try to make sense of their world, they accumulate ideas about

how things work. Klein (2,000) studied firefighters and nurses

in intensive-care units and fighter pilots. He came to one conclusion:

AThe

accumulation of experience does not weigh people down B

it lightens them up. It makes them fast.@ They have the experience to make

good intuitive decisions! They don=t have to walk through cumbersome decision-making

models or deductive syllogisms!

have to walk through cumbersome decision-making

models or deductive syllogisms!

Reflection: What role does Aintuition@ play in the things you Aknow@? Do you think it should have a role to play in research? In Adoing@ science? What would you think if you heard a physicist say, AI need to develop my physical intuition?@

Revelation

Another stream of thought

that emerged during the Enlightenment was the idea that a supreme

being, God, would speak to human beings. You might not feel comfortable

with this idea in a discussion about sources of knowledge, but

one effect of living in a postmodern world is that even scientists

are talking about spirituality and things thought to be sacred.

Reason (1993) in an article entitled, Reflections on Sacred

Experience and Sacred Science suggests that Aa secular science is inadequate for

our times and points to the pressing need to resacralize our experience

of ourselves and our world.@ (pg. 273). The contemporary interest

in spirituality may be best captured in a recent Educational Leadership

special issue dedicated to the topic. ( ) Gardner (2001) said

APhysics

and biology have no more important a role to play in our understanding

of human consciousness than ethics or religion@ (pg. B10). The major contribution

of the reformers leading up to the Enlightenment was a realization

that apart from the a uthority of the church, people could

know God.

uthority of the church, people could

know God.

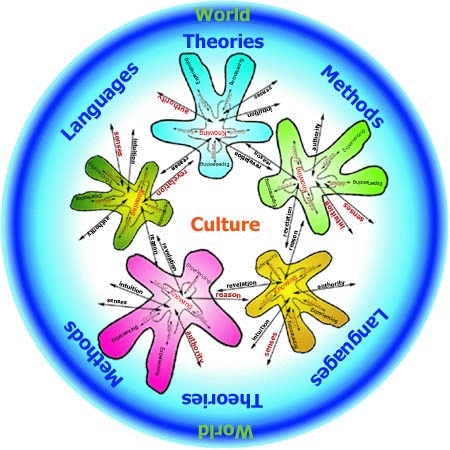

Several concepts the model tries to capture are critical. First, one source of knowledge may not be an adequate portrayal of a phenomenon. Revelation alone would likely lead to fanaticism, the senses alone to epicureanism, reason to rationalism, authority to some kind of totalitarianism and intuition to possibly solipsism. Each may contribute to an understanding of the whole. Gardner (2001) suggests a continuum of Aforms of explanation@ from the biological sciences at one end of the continuum to religious, moral and artistic at the other end. Is science concerned with only rationalism and empiricism? Reeder (1964) suggested that Aperhaps the great achievements that have resulted from the increased use of the scientific method of investigation can be attributed to the fact that it has successfully combined all of the methods of acquiring knowledge.@ (pg. 104)

Second idea B let=s revisit Locke=s notion of reflection. This is a process that could happen by virtue of an internalized dialogue. We have all experienced times where we talk ourselves through a situation until we have made Asense@ of why things occurred the way they did. There is a burgeoning literature on reflection, but recent research has shown a connection between reflection and dialogue. Reflection and critical thinking reach higher levels when a person dialogues with another person (Van Horn, 2000). So, consider the possibility that higher levels of understanding (knowledge) can be acquired by having people with different perspectives come together and dialogue (not debate). Flick (1998) differentiates between dialogue and debate by suggesting that in dialogue Aunderstanding@ is the key outcome. People are committed to trying to understand another - not convince them.

We come together as seekers/scientists/philosophers. Driven

by an innate need to understand our world, compassion/love for

a more humane existence, and hope/confidence that we have a personal

role to play, we come to the conversation/dialogue with expectancy.

We each bring life experiences and preferred ways of knowing.

No one is an island. We are not alone as we think, hear, speak,

love or admisre beauty. We dialogue. And each is changed by the

process. A group culture is established. But this happens within

the influence of theories, beliefs and cultural norms. And that

is the subject of the next section!

Further Exploratory Activities:

1) Exercise your documentary analysis skills by reviewing two definitions of Ascience@ - one from An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) (full text below), and another from a current dictionary. What can you learn about Ascience@ from the way the word has evolved over time?

SCI=ENCE, n. [Fr. From L. scientia, from scio, to know; Sp. Ciencia; It. Scienza. Scio is probably a contracted word.]

1. In a general sense, knowledge, or certain knowledge; the comprehension or understanding of truth or facts by the mind. The science of God must be perfect.

2. In philosophy, a collection of the general principles or leading truth relating to any subject. Pure science, as the mathematics, is built on self-evident truths; but the term science is also applied to other subjects founded on generally acknowledged truths, as metaphysics; or an experiment and observtion, as chimistry and natural philosophy; or even to an assemblage of the general principles of an art, as the science of agriculture; the science of navigation. Arts relate to practice, as painting and sculpture.

A principles in science is a rule in art. Playfair

3. Art derived from precepts or built on principles.

Science perfects genius. Dryden

4. Any art or species of knowledge.

No science doth make known the first principles on which it buildeth. Hooker

5. One of the seven liberal branches of knowledge, viz. Grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. Bailey. Johnson

[Note. - authors have not always been careful to use the terms art and science with due discrimination and precision. Music is an art as well as a science. In general, an art is that which depends on practice or performance, and science that which depends on abstract or speculative principles. The theory of music is a science; the practice of it an art.]

2) Read Galileo=s Daughter (2000) by Dava Sobel. Try to understand the societal context surrounding Galileo=s scientific discoveries. Make connections between your own context and your research agenda.

3) Read The Sokal Hoax (2000) edited by the editors of Lingua Franca. This is a collection of reactions to physicist Sokal=s article ATransgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity@ in Social Text (1996). In one bold action, Sokal thrust the academic debate about what constitutes science into the public arena. Other books along the same line are A House Built on Sand: Exposing Postmodernist Myths about Science edited by Noretta Koertge and Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals= Abuse of Science by Alan Sokal. Think about how we arrived at these crossroads and wonder about where we are going!!

4) Evaluate several encyclopedias for their description of The Enlightenment, The Scientific Revolution, The Age of Reason or The Age of Rationalism. Use American and British versions of different publication dates. In what ways are they the same and different? How might this be explained?

5) In Thomas S. Kuhn=s (1962), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn showed that science was really not about the pursuit of objectivity and truth, but rather simply problem-solving within belief structures or paradigms. How does a researcher Asee@ beyond belief systems? How does one figure out what his paradigms are? Is there objectivity beyond personal paradigms?