BACKGROUND

This section provides background information in the form of a discussion of the identities that are discussed in this text. The background information discussion provides insights in the form of memories of early experiences that I consider to be foundational in my understanding of my own identities. This discussion is not meant to be an exhaustive treatise on all of the ways that I identify myself or am identified. Rather, the background information provides points that are salient to the present autoethnographic study.

Specifically, this background information highlights crucial moments in my identity formation and relationship to society. Given here are three of my earliest memories of being aware of my own identity in relationship to the world around me. Those early experiences have shaped the course of my thinking and my life. They are briefly told here as a preamble to the particular experiences under close examination in this study. The memories are not shared here in chronological order or even necessarily in order of importance or impact. They represent important points in identity formation as a Black male, Christian Seventh-day Adventist, jazz avant-garde leader.

Along with those early experiences, I share briefly and broadly a characterization of my experience as an undergraduate music student at Andrews University. I relate that experience because it serves as an important link between my Black male and jazz avant-garde identities and leadership experiences as a Christian Seventh-day Adventist. Andrews University has served as a starting point and as a laboratory for my leadership experiences. In many ways, as will be discussed in a subsequent section, I feel that I have come full circle at Andrews University.

First Piano Lesson

I have been trained from the earliest age to be creative and unconventional. There are few things that make that point better than my first piano lesson. I started playing piano around the age of four or five years which is about the time that, I believe, many children might begin. Martha Baker-Jordan calls children of that age “pre-piano" (Baker-Jordan, 2004, p. 4) because they might be experimenting with the instrument but not yet engaged in formal lessons. I remember watching my father and my mother play the piano in our living room. I remember sitting at the piano and attempting to imitate what I saw them doing.

My imitation of my parents reflected an interest in making music. Developing interest can be thought of as essential in creative identity formation (Beghetto, 2021; Hidi & Renninger, 2006). For me that interest was born out in a creative identity informed by the jazz avant-garde.

It was about this time, around the age of four or five years, I remember sitting at the piano, experimenting, playing what I thought was a great tune. My father approached me and asked me if I wanted to learn to play the piano. I answered in the affirmative. I remember being so excited that my father had noticed me and what I was doing. I was thrilled and ready to absorb whatever he would show me. Reflecting on that moment, I can honestly say that what came next was the most impactful [music] lesson I have ever experienced. Before I knew what was happening, my father picked me up and placed me inside the Story and Clark baby grand piano in our living room. His words to me have remained with me both in memory and in life practice. “Play,” he said, “just play!”

That music lesson filled me with joy and a sense of infinite possibility. In that moment it seemed that nothing could stop me. What child would not be inspired by such a lesson! After all, not only did I have license to be inside a piano but my wildest musical imaginations and experimentations were being validated at the highest authoritative level of which I was aware at the time. From that moment on, I have spent my lifetime attempting to both receive and give that sort of validation – the assurance that the best thing you can do is “just play” and that if you do, the music will be beautiful.

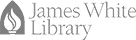

The idea of “just play” is something that I return to throughout my life. For me it is bound up with the idea of creative identity and “possibility thinking" (Craft, 1998). Cremin, Burnard and Craft (2006) suggest that possibility thinking is essential to creativity and that fostering possibility thinking should be a key part of the teaching and learning enterprise. Those same authors propose a model of pedagogy and possibility thinking that is visually represented as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Cremin Model of Pedagogy for Possibility Thinking

(Cremin et al., 2006, p. 116)

That model aligns directly, if not perfectly, with my first piano lesson and other experiences with myself as the learner and my father as the teacher. In my own experience, the “enabling context” was the “just play” attitude that my father brought and engaged with me via his own experiences with jazz music broadly and, more specifically, with the jazz avant-garde.

Sights and Sounds

My early years were filled with music of all sorts. First, at home both my mother and my father were playing the piano. My mother worked out hymns and gospel melodies. My father alternated between extended chords, bebop lines and free experimentation. In the homes of family members, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, there was vibrant singing, soulful instrumental music and lively recorded music. At church there was all manner of music, both sacred and somewhat less sacred.

And then there were the visuals that went along with the music and the musical scenes. I remember the first time I went into a nightclub. I was probably seven or eight years old. It was in the middle of the day, I went with my father who, apparently, had some business in the club that day. I remember entering the club; it seemed so dark compared to the daylight we had just exited and yet the room seemed very spacious, if not cavernous. I remember seeing the dim lights in the club and the bright lights on the jukebox. I was fascinated by the flashing lights on the jukebox. Then there was the architecture and acoustic features of the philharmonic concert hall. I started attending concerts around the same time. The shape of the room, the flying sound baffles, the colors (natural wood and neutral grays) inspired a sense of wonder and curiosity in me.

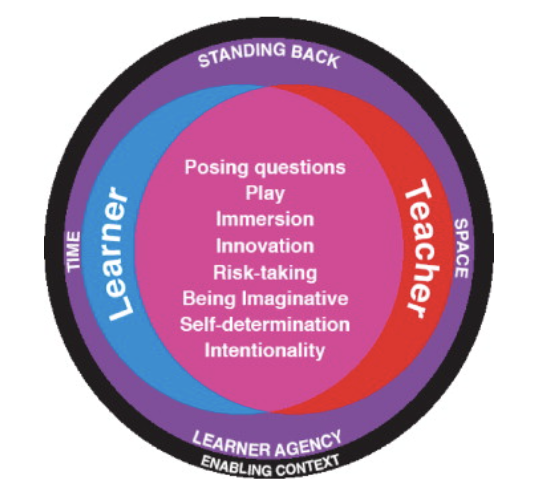

I estimate that among the most profound sight and sound experiences that I experienced as a child was associated with the music of John Coltrane. I have vivid memories of the music and cover art from two John Coltrane albums that were in our home. One album, “Crescent" (Coltrane, 1964c) features a lively tune entitled, “Bessie’s Blues." (Coltrane, 1964b) that I enjoyed hearing because it sounded so much like my house. I mean, my father played the saxophone. I remember hearing my father, amid the screeching and squawking of the free playing he did, endlessly quote the opening of the Coltrane version of "I Want to Talk About You:"

(Eckstine, 1958)

It was that Coltrane sound that my father was reaching for; “I Want to Talk About You” and "Bessie's Blues" was, and in many ways is the sound of home for me.

(Coltrane, 1964b)

Then there is the sight of the photo of Coltrane on the Crescent album cover. In my mind the man in that photo loomed larger than life. The power of the pose, the intensity of the expression, the colorization of the photo all contributed to a sense that there was something otherworldly about the music.

One aspect which seemed to solidify Coltrane’s authority as a force of musical nature was the mouthpiece as pictured in the photo. The mass, density, and hardness of that Otto Link mouthpiece was in my mind the centerpiece of the photo, the centerpiece of my musical imagination. In my mind this is what music, life and leadership ought to be unwaveringly safe, solid and authoritative.

A second Coltrane sound and sight combination made an equal and equally lasting impact on my young mind. The sound is from what is, perhaps, his most well-known recording, “A Love Supreme" (Coltrane, 1965b). Coltrane takes up the title in chant-like singing in, “Acknowledgement,” the first movement of the suite:

(Coltrane, 1965a)

As a child, I was not consciously aware of Coltrane’s stated motivations for making the music in this recording. I only learned much later in life, when I was in my 20s, that Coltrane was reaching out to and praising God, the Supreme Creator, in this music. However, the impression that was made on my child mind was unmistakable and irrevocable. I felt that there was a certain magnet-like force that drew me into the music. As with the music and visual of Bessie’s Blues, there was an incontrovertible authority in this music – the deep tones of Coltrane’s voice and the urgency in the instrumentals gave the music purpose and direction. I could feel the pull of that purpose and felt the pull of that direction. To this day, that depth of spirituality is the musical aspiration of my soul.

The image which I most closely associated with the musical suite, “A Love Supreme,” is the cover photo of John Coltrane for the album.

Once again, the intensity of the expression was, at once, scary and awe inspiring. I remember having child thoughts that ran along the lines of:

Why is Coltrane so angry?

Why is my dad so angry?

This is a Black man

This is how black men look

This is how black men should look

This is how I should look

Black people should be angry

Black people are being killed

Stuff is burning all around

That is why Coltrane is angry

Because Black people are being mistreated

That is why my dad is angry

Black people want freedom

That is why Coltrane is angry

That is what this music is about

It is about freedom

It is about Black people

Black people and freedom

That is why Coltrane is angry

I should be angry too

There is no information from Coltrane, or any other source, that the Love Supreme composition or album cover photograph had anything to do with anger, racial or otherwise. In fact, the album liner notes, written by Coltrane himself, state clearly that the music is Coltrane’s thank offering to God for leading him through a “spiritual awakening" (Coltrane, 1965b). However, in my child mind, there must have been a connection between the talk about race issues that permeated our home and the general social environment in 1960s America. I was not aware at that time that Coltrane had, around the same time as Love Supreme, composed and recorded “Alabama" (Coltrane, 1964a), a memorial to the three young girls who were brutally murdered in a terrorist attack on the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama (Early, 1999). For me that Love Supreme photograph was, and is, part and parcel of my identity, my Black identity, my Black male identity.

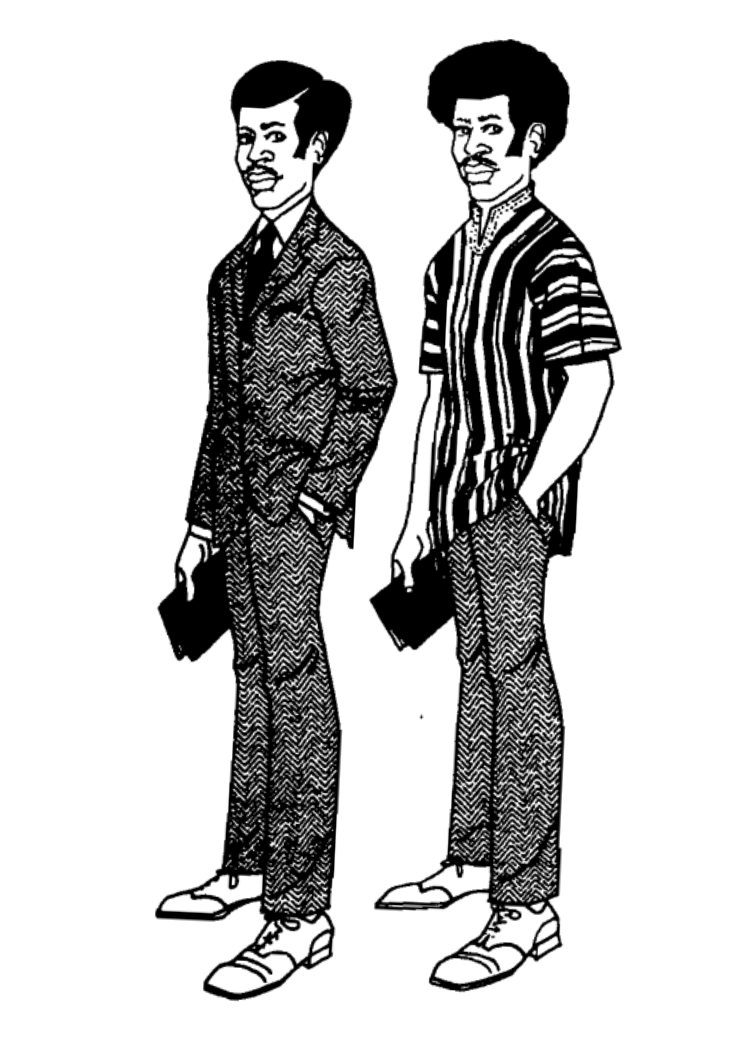

There are several leading historical theories of Black Identity. Among them is Nigrescence theory, which is derived from a term that means “becoming Black" (W. E. Cross Jr, 1994, p. 120). Nigrescence theory, was first articulated by William E. Cross, Jr. as the process of moving from identifying as “negro” to identifying as “Black" (W. E. Cross Jr, 1971). That process and its attendant semantics (e.g. negro, Black) are bound up with the politics of the times (Jackson, 2012) as is literally illustrated by the drawing that accompanied the original Cross (1971) article in the July 1971 issue of Black World:

(Cross, 1971)

Cross’(1971) original Nigrescence theory is framed in stages:

1. Pre-encounter - Perspective that the world is “non-Black, anti-Black, or the opposite of Black" (1971, p. 15).

2. Encounter - A “verbal or visual” event that “shatters the person’s current feeling about himself and his interpretation of the condition of Blacks in America" (1971, p. 17).

3. Immersion/Emersion - Immersion into everything Black; rejection of everything white. “emergence from the dead-end, either/or racist, oversimplified aspects of the immersion experience" (1971, pp. 18–20)

4. Internalization - “Inner security” and satisfaction with the self as Black (1971, p. 21).

5. Internalization/Commitment - Acting in a principled fashion that comports with a “new self-image…eventually becomes the new identity" (1971, p. 23).

Cross is joined by other theorists (Helms, 1990; Jackson, 2012) who view Black identity as developing in stages, perhaps in somewhat different terms but in stages nonetheless. While I understand the stage approaches, which I believe are all somehow beholden to Erikson (1994), none of them align with my own experience. That is, I was aware of identifying as Black at a very early age. I have never been comfortable with the oppressive circumstances that I have faced as a person of color. Nevertheless, I have always felt comfortable being who I am, that is a person who is Black. That is to say, as far as I am aware, I have from the youngest age believed and acted in ways that could be identified as internalization-commitment (W. E. Cross Jr, 1971) or internalization (Helms, 1990; Jackson, 2012). None of the other stages register with me as salient to my personal experience.

Interactions with society via home and community provided me with a strong sense of self during my early years. My mother, father, and other family members explained to me that race was a construct that was ascribed to me. In other words, I was a Black person because the dominant social class said I was a Black person. They followed that explanation with the admonishment that I should be proud to be Black, even in light of any apparent disadvantages. Illustrative of this is a picture that I had drawn in my kindergarten class. The person in the picture had characteristically “white” features – long straight hair and light skin. My father told me that I should draw Black people. He said that Black people were beautiful and that I should be proud to be Black and represent Blackness in my artwork.

The interchanges between my family and the community also instilled in me a positive commitment to Black identity. Here I see Jefferson Avenue, the main thoroughfare in the Black community in Buffalo, New York, as illustrative of those interchanges. The presence of my family or the presence of the avenue, either on or within a couple blocks of the avenue, was a constant. My paternal grandparents and my maternal great grandparents lived there. My maternal grandfather operated an auto repair shop on the avenue. My uncle operated two beauty supply shops on the avenue. The seventeen children of my Aunt Lula and Uncle Edgar, formed their own Gospel choir – everyone knew the Gayle Family Singers. Hardly a day went by when someone in the family did not go to or talk about the Pine Grill (a jazz music venue where my father spent most of his time away from home) and GiGi’s restaurant (the best soul food in town). A walk on the avenue invariably meant seeing and interacting with people who you knew and who knew you. Jefferson was the hub of the Black community. Black families, Black businesses, Black culture. Black community thrived on the avenue. My family was part of the community and the community was part of my family. There I derived a tremendous sense of Black identity.

Additionally, I saw my family as successful participants in the Buffalo community. As mentioned above, my uncle and maternal grandfather were successful shopkeepers. My paternal grandfather built a solid middle class existence – he was a homeowner at a time when few Black people were homeowners – through years of labor in the steel mills. Also in the family was a doctor and several teachers. My grandmother was treasurer of one of the largest Black churches. My uncle was a successful contractor. Also important were the associations my family had with the University at Buffalo. There my mother supported the admission of Black students through the Equal Opportunity Program, my father was a music professor, my uncle was part of the arts scene as a musician and as a radio host with a jazz program on the university radio station, and I watched my aunt work from undergraduate student to Dean of the Graduate School of Education. Perhaps the greatest impression on me as a young person was my mother as a partner and manager of a Black woman owned court reporting business. That was not in Buffalo but it was vital to my understanding of my Black identity. These and other family members not only confirmed my Black identity but also provided exposure to Black leadership across a variety of settings both within and outside of the Black community.

Finally, circling back to Jefferson Avenue, the Emmanuel Temple Seventh-day Adventist church was part of the avenue community. That church is probably the single place, apart from family and school, where I spent the most time. There I was impressed by the preachers, the strong Black leaders whose sermons were at once poetry, prose and dramatic performances that inspired hope in the hearts and minds of their hearers. My family helped me understand that these pastors were not only religious leaders but they were also organizational leaders and intellectuals, Black thinkers whose wisdom was to be both admired and emulated as a matter of successful navigation of life as a Black person. Then there was the music of the church, into which flowed seemingly every stream of the art – anthems, hymnody, Gospel, classical, soul, jazz and almost everything Black people produced. Led by the Willis and the Weathington families and engaged by a multitude of vocal ensembles, soloists and non-vocal instrumentalists, the music produced in me both spirituality and a cognition that Black people were, on this earth, without peer in the creation and performance of the art of sound. Finally, the teaching, relationships and camaraderie that were part of the social life of the church were developmentally affirming of my Black identity. Sabbath school teachers exercised excellence and care in education. Adult parishioners, who at times seemed overly concerned about decorum, nonetheless lovingly provided care, advice, and social opportunities – church social gatherings were frequent, fun and filled with delicious food. And the time that I spent with my age-peers were growth opportunities that produced lifelong friendships. It is difficult to overstate the impact that the church had on my Black identity. The church gave me the sense that Black people were great people and that I belonged to those great people.

Another perspective on race identity is drawn from the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI)(Sellers et al., 1998). The MMRI examines the importance of race to a person's idea of self and the meaning of membership in a racial group.(Sellers et al., 1998, p. 23). There are four key points in the model:

1. “...identities are situationally influenced as well as being stable properties of the person" (Sellers et al., 1998, p. 23);

2. People have multiple identities that are arranged by rank (Sellers et al., 1998, p. 23);

3. “...individual’s perception of their racial identity is the most valid indicator of their identity" (Sellers et al., 1998, p. 23);

4. MMRI is concerned with identity “status” rather than identity “development" (Sellers et al., 1998, p. 24).

The foundational concepts of the MMRI seem like a better lens by which to examine my own identity. Looking back and reflecting on my early experiences, and carrying that reflection right up to the present moment, I am able to understand that there have been many influences to my identity such as family, schooling, church and musical culture, as illustrated in my early experiences and time as an undergraduate student. At the same time, I can honestly say that there has never been a time when I questioned the centrality (Sellers et al., 1998) of my racial identity or felt that my membership in the racial group was somehow unimportant. In fact, I took the instrument designed to measure MMRI, the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers et al., 1998) and was struck by one of the scale questions. The question reads: “My destiny is tied to the destiny of other Black people.” My reaction to that question is: Of course my destiny is tied to the destiny of other Black people! What else would it be? That is one of the greatest lessons that I learned from the sights and sounds of the Coltrane albums –

I am who Coltrane is

he is who I am

we are Black

Black men

we are Black people

bound together for life

and for death

This music is Black music

it is who I am

I am what it is

The music of Black people

that is who I am

In addition to my Black male identity, the thought that I am the music, particularly the jazz avant-garde, has also been with me since I was very young. Monahan (2020) describes such a representational claim as musical identity (Monahan, 2020, p. 49).

Musical identity can be thought of as specific associations with musical activities, musical instruments and musical genres (Hargreaves et al., 2002). My own musical identity centers around the musical activities of composition, performance and teaching. Additionally, from a genre perspective, I identify as the jazz avant-garde. While I would prefer a term other than “jazz” to describe the genre (Payton, 2011, 2013) with which I identify, the term has a certain practicality as a reference point from which to engage in conversations and representations of who I am. By contrast, saying I am a “post modern New Orleans- or avant-garde New Orleans (Payton, 2011) musician has obvious limitations for general recognition or understanding. Consequently, I self-identify as a person/musician in the jazz avant-garde tradition.

A Vision of Leadership

As stated at the outset of this work, I identify as a Christian. I consider it my utmost privilege to be blessed by God to live, and move, and have my being in Him and to be able to offer any little thing that might be of benefit to the people with whom the Creator places me in contact. My closest association with organized religion has been with the Seventh-day Adventist church. That association with the church has been lifelong, essentially from birth until the present day. My mother is to be credited with mostly, if not entirely (on a human basis) for my association with the Seventh-day Adventist church. She made sure that I was in attendance at church services at least once a week, mainly on Saturday, from birth through adolescence. Moreover, while I say that my association with the church has been lifelong, there have been significant periods of time in which my adherence to Christian faith principles and/or doctrines of the church have left more than a little to be desired. In spite of, or perhaps because of, my shortcomings, my mother has never ceased to offer fervent prayers to God on my behalf. Again, to the credit of my mother, I am able to advance the claim that I am still alive and associated with the Seventh-day Adventist church.

It is in the context of attending church with my mother that the third and final memory is situated. I was about three or four years old. It was a fairly typical Saturday. We went to Emmanuel Temple Seventh-day Adventist church on Saturday at the large 19th-century red-brown stone edifice at the corner of Peckham and Adam streets on the east-side of Buffalo, New York. Even to my young mind, the acoustics of the sanctuary seemed perfect for musical performance. The sounds of voices and instruments soared and reverberated through the room with little or no artificial amplification. This Saturday was not different.

The choir was singing a feature piece. Brother Willis was directing the choir. I was sitting in one of the front rows near the piano on the left side of the sanctuary next to my mother. I do not remember what piece the choir was singing but I do remember that it sounded very good. The room seemed to be lit more brightly as the choir sang. I remember hearing congregants behind me making verbal exclamations of praise and affirmation: “Yes!” “O yes!” “Hmmmm!” Some people were even singing along with the choir.

At that moment it seemed to me that I could, and even should, be doing what Brother Willis was doing. I mean, he was leading the choir. The singing was beginning to pick up a bit. Surely, the whole arrangement would benefit from an added lift from a gifted three-year-old conductor…Before the thought had fully crystallized in my imagination, I was on my feet, standing on the front pew, waving my arms excitedly, enthusiastically, expressively directing the choir behind Brother Willis.

I am not sure exactly how long that shadow directing experience lasted. And I do not remember the expressions on the faces of any of the choir members – they must have been at least a bit amused, if not inspired. I don’t remember seeing Brother Willis after the song had ended – surely he had felt the extra lift from my participation. My clearest memory of the ending was my mother, with no hint of amusement or approval in her face or in her body language, escort me down a side aisle, out of the sanctuary, to a small room off the narthex where the choir robes were stored. I will spare the reader the fine grained details of the subsequent events. Suffice it to say that, the foregoing approbation of my mother notwithstanding, the concept of gentle parenting (Grady, 2019) was unknown to her in such circumstances. My mother has a more upbeat memory of the ending. She remembers being thrilled to see her “precocious” (her word) child participating energetically in the music. That said, she did confirm that she and I had spent time together in that room off the narthex on several other occasions.

That experience was indelibly impressed on my mind as to the power and possibilities of music, particularly in a religious context. That choral performance inspired me then and that inspiration has never left me. I have long sensed that the sound of a large group of singers, whether under specific direction as in a choir or in a congregational context, is unmatched in might and majesty. And by extension, music making in unbridled praise and adoration of the Creator, God Almighty is one of, if not the highest form of expression known to humans. Whatever it is that underlies and fuels such expression is the thing that I want to motivate my every action, musical and otherwise.

Starting Points for Leadership

Those memories of my early experiences are what I know to be my first conscious bits of identity formation as a Black male, a Christian Seventh-day Adventist and a creative in the tradition of the jazz avant-garde. They also form the basis for my disposition as a leader. In other words, my understanding of how leadership is best lived out in my life is as a creative risk taker whose approach and understanding of life circumstances is informed by the dynamics of race, religion, and music.

Race

With respect to leadership, there is one other background circumstance that I will introduce at this time. That circumstance was my time as an undergraduate student at Andrews University. To tell the story of my undergraduate experience, with all its parts, is beyond the scope of the present study. That being said, this discussion will focus on the whole experience, categorically, as preparation for leadership in music.

As an undergrad, I declared a double major in religion and music. Ultimately, because of lack of resources to complete both degrees, I graduated with a major in religion and a minor in music. The breadth and depth of my music study during that time was well beyond the course of study prescribed for any undergraduate degree, either major or minor. In addition to the required coursework and performance ensembles (select vocal octet, university chorale, singing men, wind symphony, vocal quartet), I studied three instruments in-depth: piano, trumpet and voice. I maintained a regular schedule of performances at campus churches, local churches, regional churches and national and international places of worship. Additionally, I independently led groups and organized, promoted and performed solo concerts on and off campus; I directed a local church choir; and I arranged and composed music for instrumental and vocal ensembles. I also organized, directed and arranged for a jazz big band that won grand prize honors in the university talent competition.

Most significantly, I studied more music history, literature and style than my peers, not because I am an academic overachiever but because I was struck by the complete exclusion from the curriculum of the contributions of or any mention of Black artists. When I raised the issue with one of my professors, he was “generous” enough to say that I could study artists that were not included – however, that was not a replacement for the artists in the curriculum, it was in addition to. The net effect was that I had to do double or triple work in order to obtain and present the knowledge that was missing in the curriculum. One example, there were no books or other resources in the school library on Black jazz artists. That was before the Internet and the wide access to literature afforded by the world-wide-web. Consequently, I had to travel to or send for work from other libraries, sometimes many hundreds of miles, in order to obtain the information necessary for my schoolwork.

I refer to that last experience as most significant because it, along with many others, highlights the tension that I felt, and still feel, as a Black male, Seventh-day Adventist, jazz avant-gardist leader. I believe that there was an intentional effort to exclude Black music, especially jazz from Seventh-day Adventist spaces. That effort has been particularly hurtful to me because I am a Black man whose identity is bound up in Blackness, Adventism and jazzness. While I was an undergraduate music student, I became aware of a statement created by the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists (1972), that outlined 10 principles of music for the church. Those principles were followed with this statement: “Certain musical forms, such as jazz, rock, and their related hybrid forms, are considered by the Church as incompatible with these principles" (General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, 1972).

Again, for me and my identities, that statement is particularly troublesome. I try to be a faithful Christian. And I also am painfully aware that my identities are entirely bound up with being Black and immersed in jazz music culture. I have lived with this pain for most of my adult life. There is a painful tension between being true to myself and my racial and creative identity and the reality that most of the people in the faith community are either entirely unaware of my identity or choose to discount my identity or, worse, see me and what I do as “incompatible” with the principles of the church.

As I embarked on this research project, I was fully aware that this tension is still part of my daily consciousness. As a reflexive research practitioner, I knew that I would have to not only acknowledge the tension and its source but also navigate the effects of the tension in my research. For those reasons, I chose to start the research project (after gaining IRB approval) in Hamel Hall which is the place that I consider to be the launch pad of my leadership experiences in this project. I started to explore and record my thinking about my past there, about the autoethnographic research which I was about to undertake, and about my current circumstances. Before I play, I think: Who is listening? Play quietly. Play cautiously. Play inside. I resolve to play inside. I start playing. I play outside. But cautiously outside. I use idioms and motifs that will be familiar to those classically trained or narrowly minded who might hear or listen. And I use a theme from the Black musical tradition, “I Want Jesus to Walk with Me” that is my earnest prayer for working through this research project.

Why do I play so cautiously? Because that statement about “incompatibility” never leaves my mind. That statement is especially prominent in my mind whenever I perform in this place, because the man whose name the building bears was one of the chief detractors of jazz music in the Adventist church (Hamel, 1973). Because I don’t want to be branded? Because I don’t want to be dismissed? This is it: because this audience might hear and not understand, they might say it is nonsense and perhaps even evil. They might say that I am evil and push me out farther than I already am. They might push me out of my insecure place in the organization…out of my job…I want to be a good Christian. For a long time I might have conflated being a good acceptable Adventist with being a good Christian. I have always wanted to share the Gospel of Jesus Christ via the musical culture that is my home.

I will take a moment here to bring the idea of intersection into the conversation. Throughout this project I use the term “intersection” to draw together several conceptualizations of identity, namely racial identity, sexual orientation, gender identity, religious identity, and cultural (musical) identity. That term, “intersection,” is meant to elucidate the complexity that emerges when multiple identities meet in societal pathways that are at once divergent and convergent. While it may be possible to analyze any one identity in any path in isolation, it is, for all intents and purposes, impractical, if not impossible, to do so. For example, a look at median annual earnings in the United States since 2010 (United States Department of Labor, 2022) reveals that earnings for all men is greater than for all women. Earnings for Black men are always less than for white men and sometimes less than white women. And earnings for Black women are always less than for white men, all men, Black men, all women, and white women. Hence, we see that if we look at only median earnings (path) for men (identity) we might come to the conclusion that men always earn more than women. However, when we look at the combination (intersection) of race and sex, we see that another conclusion is drawn – Black men may earn less than white women. Kimberlé Crenshaw highlights the intersection of marginalized identities as “compounding" (National Association of Independent Schools, 2018). That is, there is never a time when a Black man is only Black or only male; he is always both Black and male. And the situation is even worse for Black women. The same data referenced above (United States Department of Labor, 2022) show that Black women consistently earn less than white men, white women and Black men.

Crenshaw (1989) laid the conceptual foundation for the concept of “intersectionality.” She makes the case that identities do not exist in isolation and that they are best understood by examining their intersectionality and how people in their intersectional identities are impacted by social constructions (e.g. race and gender) and institutions. Crenshaw succinctly explains intersectionality in the following video:

(National Association of Independent Schools, 2018)

For me the disadvantage in society that I face as a Black male (Chetty et al., 2020; Lyons & Pettit, 2011; Reeves et al., 2020; Sidanius & Veniegas, 2013; Umberson et al., 2014) has been in the forefront of my consciousness for as long as I can remember. Intersectionality and identity are discussed further in the experiences section below.

Religion

I understand my religious identity as emanating from interactions with individual persons and groups of people. For me, religious identity means claiming membership in a particular religious group and representing that claim by adherence, both internally and externally, to the tenets or foundational beliefs of the group. In my case, the religious group with which I most closely identify is the Seventh-day Adventist church.

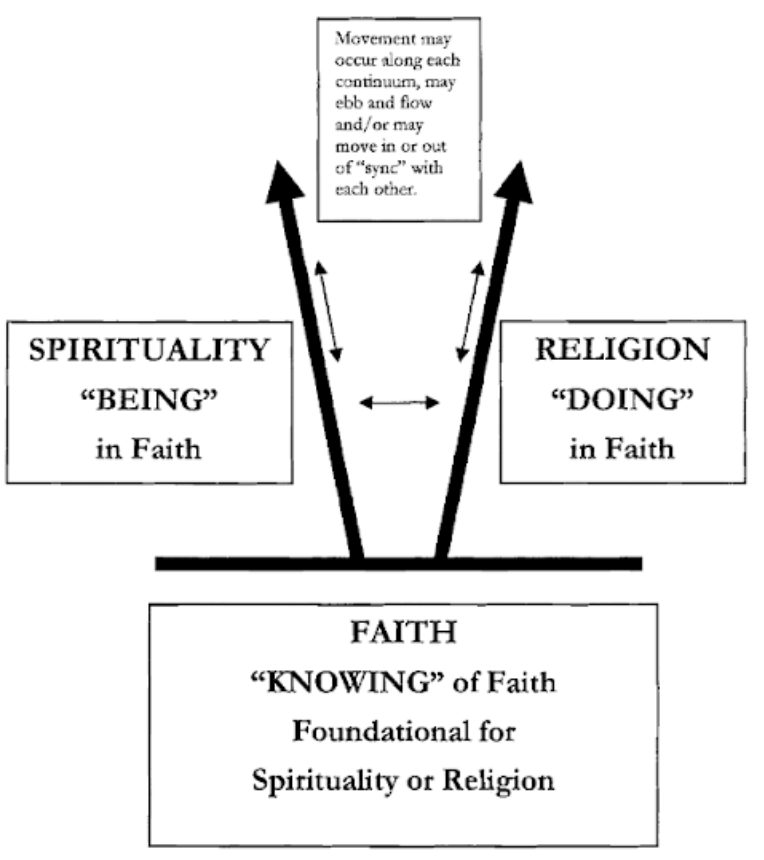

Before discussing religious identity further, I will mention that I make a distinction between faith and religious identity. I understand faith to be the belief that is held in or about an entity or idea (l). Whereas, I understand religion as an expression of faith. Newman (2004) makes a similar distinction, including both religion and spirituality as outgrowths of faith. An understanding of such associations may be derived from this visual model:

I have a personal belief or faith in Jesus Christ as the Almighty God, preexistent, incarnate, loving, life-giving and life-saving. It is impossible to say that such a faith is entirely distinct from religion or religious identity. At the same time, I believe that my faith is independent of my religious identity. A thought experiment that makes the point: if the Seventh-day Adventist Church were to somehow dissolve as an organization, I would, necessarily, no longer be a member of that organization by virtue of the fact that it would be impossible, if ridiculous, to claim membership in an non-existent organization. However, I could, and I believe I would, maintain the same personal faith in Jesus Christ.

As described above my religious identity is largely a result of my action and interaction with people. From the earliest age, my mother has been the greatest influence in my religious identity. Before I was fully able to decide upon or engage independently in religious group associations, my mother faithfully took me to church. As a member of the Seventh-day Adventist church, my mother made sure that every Saturday, I attended Sabbath School meetings and worship services. Additionally, she encouraged me to participate in church meetings and activities that were specifically oriented to children and adolescents.

The emphasis my mother placed on church attendance and participation was important for her and for me. As a child, family and church were at the center of our existence. My mother participated in a number of social groups in the church. She was active as a board member and organizer of church activities. Her most prominent, and perhaps most important, role was as a church musician. She played the piano to provide music for worship services and all manner of church meetings and gatherings. She both sang in and accompanied choirs, small ensembles and soloists both in the church and for performances at other churches and public venues. Growing up, I was frequently with my mother at some musical event, rehearsal, board meeting or church social event.

From childhood through my teenage years, I developed many great relationships with peers and adults in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. From worship services to youth meetings to roller skating to nature outings to visits and parties with people in their homes, the church community was, more or less, at the center of my activities. For most of my K-12 education, I attended schools that were not church sponsored. Consequently, apart from school, church and church community was where most of my time was spent.

All of the above influences on my religious identity are overshadowed by one event, the official entry of my membership into the Seventh-day Adventist church via baptism. Adventists practice baptism by immersion for individuals who are of age to make a reasonable choice to publicly affirm faith in Jesus and a desire to join the church. I was baptized at the age of 10 years. After baptism I was officially a member of the Adventist church. Since that time I have self identified as Christian Seventh-day Adventist.

Charles Glock and Rodney Stark advance extensive discussions of religious identity founded on five dimensions: experiential, ideological, ritualistic, intellectual, consequential (Glock & Stark, 1965) or belief, practice, knowledge, experiences, and consequences (Stark & Glock, 1968). Although the names of the dimensions appear to be different, their defining content is effectively the same. The second set of dimension identifiers is a revision of the first set by the authors to provide clarity (Stark & Glock, 1968). The first set is included here because it provides insight about the original intent or meaning of the dimensions and it provides useful levels of abstraction. The following discussion briefly summarizes each dimension and then relates the dimension to my own experience.

The belief or ideological dimension encompasses the “expectations” that the members of the religious group will subscribe or adhere to certain “tenets” of the religion (Stark & Glock, 1968, p. 14). Seventh-day Adventists hold a set of 28 “fundamental doctrines" (General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, 2018, 2022). I affirm that I accept the official doctrines of the Seventh-day Adventist church. However, as described above, the interpreted expression of those doctrines, particularly with respect to music and identity has been a source of tension and anxiety for me. Statements forwarded and positions held by church leaders have consistently challenged my sense of personal ideology and identity as a Black male, avant-garde jazz musician.

The practice dimension is characterized by “ritual” and “devotion,” where ritual is the regular public practices of the religion (e.g. worship services) and devotion is the private practice of the individual (e.g. private prayer or Bible study)(Stark & Glock, 1968, p. 15). Among the major rituals of the Seventh-day Adventist Church are weekly worship services on Saturdays. Many churches also have some type of midweek prayer service. The rituals of the Seventh-day Adventist church have been a source of mixed blessing for me.

Church worship services and music have often been sites of inspiration and uplift for me. Growing up, I benefited from hearing and participating in a variety of choral and instrumental music, such as singing in youth choir, playing guitar and bass in a contemporary music band and accompanying singers such as Whintley Phipps and George Sampson. I also learned much about faith and doctrine through the homiletic craft of great preachers, such as Harold Kibble, C. L. Brooks, C. D. Brooks, and many more. Those same worship services and music have also been sites of frustration and confusion. For example, in one church when leading music for Wednesday evening prayer services, I was perplexed and somewhat demoralized when told that it was inappropriate to include a bass guitar along with the piano for accompanying hymn singing. In terms of private practice, I attempt to pray on a daily basis and I believe that I have done so for the better part of my days on this planet.

The experience dimension considers the contact, connection, or communication with the divine or transcendent being experienced, perceived or felt by the individual (Stark & Glock, 1968). Seventh-day Adventists encourage “communing with [God] daily in prayer" (General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, 2020). I experience the presence of God in communing with Him through music. That experience is not a one-way communication, as in me translating thoughts (musical or otherwise) and directing them to God. Rather, the communication is bidirectional – in the first place, God instills in me the impulse to seek Him and, in response to that impulse, I listen to the sounds that God gives me and offer a re-expression of those sounds to him in return. Ultimately, it is by the presence of God in me that I have life and experience every aspect of life, physical, emotional, cognitive and social.

The knowledge dimension points to the presupposition that adherents will grasp some essential information about the foundational premises or beliefs upon which the religion is constructed (Stark & Glock, 1968). On the day of and immediately before the aforementioned baptism, by which I entered into membership of the Seventh-day Adventist church, I was asked to publicly declare my assent, affirmation and/or understanding of a list of tenets of the religion. Literally, the pastor of the church asked me, and others who were being baptized on the same day, to answer aloud in the hearing of the congregation, a set of about 20 questions that ranged from belief in Jesus Christ as personal Lord and Savior to a pledges to eschew tobacco, alcohol, caffeine and other drugs or harmful substances.

Finally, the consequences dimension pertains to the “rewards and responsibilities” of religion (Glock & Stark, 1965, p. 35). In the Seventh-day Adventist church much of the emphasis on consequence centers on the rewards of salvation, particularly the promise of eternal life at the second coming or advent of Jesus Christ (General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, 2020). Historically, especially since the year 1888 when E.J. Wagonner and A.T. Jones presented to the church a theology of righteousness by faith, there has been an ongoing debate in the church as to how or whether the rewards of salvation are dependent on fulfillment of religious responsibilities (C. M. Maxwell, 1988; Pfandl, 2016; Schwarz, 1979). As a young person growing up in church, my personal understanding was that following the rules was very important, if not vital, for one to be considered a good Adventist. Throughout my life there has been a personal struggle to know if I was doing things on the right side of church doctrine, particularly with respect to music. Many times I participated in church musical activities or performances with music that I did not know or understand to represent my faith experience; I made those performances because I felt it was the right thing to do to be accepted or acceptable in the church.

As evidenced by the paragraphs above, I am able to understand and affirm my own Seventh-day Adventist religious identity through the belief, practice, knowledge, experiences, and consequences dimensions, as described by Glock and Stark (1965; 1968). At the same time, and considering the same evidence and dimensions, it becomes clear that there are certain tensions that emerge between my musical identity and my religious identity. For example, I believe and the church teaches that activities such as prayer, worship and singing praise are vital aspects of religion. I also believe that the music that I perform is both from God and a sacred expression of communication (prayer), worship and praise to God. At the same time, the church teaches that “[...] not all sacred/religious music may be acceptable for an Adventist. Sacred music should not evoke secular associations or invite conformity to worldly behavioral patterns of thinking or acting" (General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, 2004). I have been told by some Adventist adherents that my music evokes night club music. Even though my music does not bring such thoughts to my mind, such an assertion seems fair, in as much as that association might be true for another individual. Does that mean my Black avant-garde jazz music is unacceptable for an Adventist? What about the music of Messiah by George Frederick Handel that evokes Italian opera for some listeners? Or what about the Veni, Veni Emmanuel which appears in the Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal (Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1985) which evokes the music of the ancient Roman Catholic Church which Adventists forcefully keep at a theological and doctrinal arm's length (LaRondelle, 2010; Reinder, 1994; White, 1888)? Are these musics acceptable for an Adventist?

I suspect that those latter examples are considered perfectly acceptable for Adventists. Such an acceptance might suggest a bias toward certain styles of music or music that is derived from certain ethnic sources. Or the rejection of jazz might suggest a bias against Black music. Whatever the underlying cause might be, the inconsistency of acceptance has been a source of both cognitive and emotional dissonance for me. As a Black male, avant-garde jazz artist, my identity as a Seventh-day Adventist is fraught with dissonance.

Music

As I think about my jazz avant-garde identity, it occurs to me that it is difficult, if not impossible, to describe that identity with words alone, or even using words as the primary vehicle. It is after all, that identity, rooted, grounded, and extended by stem, branch and flower of music, art, and creative force. Consequently, following a few words of preface, the exposition of identity in this section is articulated in poetic and musical forms.

Informed by both a personal understanding and a widely held belief across societies and cultures that music flows from a creative impulse, I would like to first mention here that I believe my ability to make music to be a God given gift. I believe that the capacity to perform music is also a gift from God. My earliest exposure to music making and performance was, as described above, at home and at church. In both those contexts I gained the understanding that the experiences of making music and performance are spiritual experiences. By “spiritual” experience I mean music comes from a human connection to something inside the self that in turn is connected to, or perhaps even actuated by, a spiritual being that is outside the self. Essential to such a view is understanding God as a spiritual being (John 4:4). From that understanding flow experiences of music making and performance. For example, musical authors in the Bible speak of the “soul” or “heart” singing to or about God (Psalm 30:12-13; Psalm 71:23; Psalm 103:1-2; Psalm 146:1; Psalm 104:35: Psalm 108:1). Pauline letters in the New Testament encourage music making from the “heart” (Ephesians 5:19; Colossians 3:16). Other Biblical examples include humans being being inspired or directed by God in music, especially as a prophetic expression (prophecy is described as a Spiritual gift (see 1 Corinthians 12:10, Romans 12:6): Miriam (Exodus 15:20-21); Deborah (Judges 5:1); Saul (1 Samuel 10:5-5, 10-11).

The jazz avant-garde has been the music that has flowed from the deepest parts of my soul. That music is my expression of the thoughts and feelings that arise from my life. The stories of my life, my experiences with God, with people, with the creatures and things in the environment can all be told through that music. Among those experiences, I believe that the spiritual experiences are most important and best known via the jazz avant-garde. As God created me and placed me in the world, so He gave me a gift of music that is inseparable from who I am. As I am made in the image of God, a Spiritual being, so I am the expression of the music of God – and I sing His song with my whole being.

The jazz avant-garde is also widely known as free jazz (Kelley, 1999; Such, 1993; Westendorf, 1994). Sometimes a distinction between the terms is made (Gridley, 2007; T. S. Jenkins, 2004), where the jazz avant-garde is regarded as the leading edge or the experimental vanguard of the music and free jazz is viewed as a subset or genre that is subsumed by that vanguard. While such a distinction might find some ground in a philosophical debate, I make no such distinction here or elsewhere. I have always understood from my personal experiences and from interactions with my musical mentors that free jazz is the jazz avant-garde. This point is raised because the terms are used interchangeably in certain characterizations that link the music, spirituality and Black people in society. That linkage is especially important because the concept of freedom applies simultaneously to musical, spiritual and social conditions. In other words, my jazz avant-garde identity is an expression of freedom in both literal and metaphoric terms.

I believe that my identity is affirmed by scholars from a variety of approaches. Archie Shepp (1973) states it musically as A Prayer from the Album Cry of My People:

(Shepp, 1973)

Gerald Early discusses it when talking about John Coltrane in the jazz avant-garde: “…you know, jazz had always had a certain kind of religious element to it and certainly, you know when Ellington had written religious music and things of that nature. But now, it was really this kind of complete, I think the avant garde was really trying to make this kind of meld that was making jazz and spiritual music one." (Early, 1996, p. 5). “[Coltrane] combined artistic innovation with therapeutic, redemptive spirituality…It is surely no accident that during the time of Coltrane' s greatest period as an artist, from 1960 to 1967, Martin Luther King was talking about redemptive love and sacrifice as the solution to the American race problem…" (Early, 1999, p. 373).

In another place, Early (1999) takes a dim view of the jazz avant-garde, calling it “anti-intellectual” and “regressive” in the sense that it was a space for Black people to exercise exclusion and rejection of white people in a way that mimicked the rejection that Black people had suffered (Early, 1999, p. 374). There might have been some [Black] people who subscribed to such a course. However, in my own experiences with musicians and people associated with the music there was no hint of regressive attitudes or actions. I was encouraged by the community of musicians and artists to appreciate and love my Black identity and all Black people, especially in light of the rejection and dehumanizing light that in which they were cast by white society. An example of that appeal to love and appreciation is illustrated by this excerpt from a letter from Coltrane (1975/1962) to Don DeMichael, an outspoken and influential critic of free jazz:

Believe me, Don, we all know that this word which so many seem to fear today, ‘Freedom’ has a hell of a lot to do with this music…It seems history shows (and it’s the same way today) that the innovator is more often than not met with some degree of condemnation; usually according to the degree of his departure from the prevailing modes of expression or what have you. Change is always hard to accept. We also see that these innovators always seek to revitalize, extend and reconstruct the status quo in their given fields, whenever it is needed. Quite often they are the rejects, outcasts, sub-citizens, etc. of the very societies to which they bring so much sustenance. Often they are people who endure great personal tragedy in their lives. Whatever the case, whether accepted or rejected, rich or poor, they are forever guided by that great and eternal constant – the creative urge. Let us cherish it and give all praise to God. (Coltrane, 1972, p. 160-161)

Reading and reflecting on these thoughts, it is difficult to arrive at the conclusion that Coltrane was leading an anti-intellectual or regressive movement. Instead, it seems clear that he is interested in the uplift of oppressed souls.

It is also worthy of note that not all free jazz or avant-garde jazz spirituality emanates from a view of God to which Christians or Seventh-day Adventist Christians adhere. Consider for example the avant-garde titan, Sun Ra. Originally known as Herman Blount, Sun Ra appropriated the name of an Egyptian sun god, claimed to be from Saturn and represented his music to be, by turns, space music, infinity, or cosmic sound (Such, 1993; Szwed, 2020; Wilmer, 2018). Another example is pianist, composer Cecil Taylor, who has produced a range of music and poetry inspired by the so-called, “voodoo,” tradition (Grundy, 2019a, 2019b). Across the jazz avant-garde there are a variety of spiritual orientation and practices, derived from Islam, African religions, Hinduism and others (Baraka, 1983; Howison, 2012; Steinbeck, 2008; Such, 1993; Szwed, 2020).

My personal belief and religious tradition remain paramount to my identity, even at the intersection of that religious tradition and the jazz avant-garde – or perhaps, especially at the intersection of that religious tradition and the jazz avant-garde. That a good number of musicians and their music highlight or emphasize traditions that are not my own is not especially worrisome. I choose not to engage in situations that are not in alignment with my beliefs both in the Black jazz avante-garde and in other musical genres.

Continuing the discussion of affirmation of my identity and beginning with a close focus on Coltrane, the person and [his] music that are probably most well-known representatives of the jazz avant-garde, I hear the identity in his music:

Acknowledgement (Coltrane, 1965a)

The Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost (Coltrane, 1965c)

In my mind and the view of other scholars (Allen, 2007; L. L. Brown, 2010; Howison, 2012) Coltrane and his music epitomize the identity of a person wholly dedicated to using the unique gift of music given by God as an expression of the Black soul, the jazz avant-garde.

Affirming my identity with a wider focus that encompasses the views of more artists/scholars, the jazz avant-garde is inextricably fused with Black identity (Anderson, 2012; Baraka, 1983; Baskerville, 1994; Jones, 1963; Westendorf, 1994; Wilmer, 2018) and the spiritual nature of the music (Buhl, 2008; Westendorf, 1994). Of the music, Buhl (2008) writes: “‘The avant-garde’ is Giddins’s preferred term for what I have called free jazz—and I do wish my reader to experience it as music. I believe the propulsive passion and world-denying power experienced at the vanguard provide a most appropriate soundtrack for faith.” For me, these sounds, and many more like them in the avant-garde tradition, are knowledge, understanding, expression, and reflection of my own faith and identity:

Heavenly Home (Ayler, 1967)

Freedom Dance (O. E. Nelson, 1962)

Ballad for the Black Man (World Saxophone Quartet, 1991)

Jesus Christ and Scripture (C. E. Gayle, 1992)

As this preface concludes, I restate my understanding that God is the provider of all good gifts and that the gift of music is among the talents with which I have been entrusted. Among the conduits of divine giving were the artists in the jazz tradition with whom I have personally engaged or encountered at various points in my life, first my biological father, Charles Gayle, and then (in alphabetical order) Nasar Abadey, Jackie Blake, Hamiet Bluiett, Miles Davis, Joe Ford, John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, Paul Gresham, Herbie Hancock, Jerry Livingston, Joe McPhee, McCoy Tyner, and many others. Moreover, by prayer and practice and perseverance through much study and many trials, I have come to understand my place in the tradition. What follows is an exposition of my understanding of my identity, who I am and how I came to be.

Dear friends, now we are children of God, and what we will be has not yet been made known. But we know that when Christ appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is.

(1 John 3:2)

We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. Not only so, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for our adoption to sonship, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we were saved. But hope that is seen is no hope at all. Who hopes for what they already have? But if we hope for what we do not yet have, we wait for it patiently. In the same way, the Spirit helps us in our weakness. We do not know what we ought to pray for, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us through wordless groans. And he who searches our hearts knows the mind of the Spirit, because the Spirit intercedes for God’s people in accordance with the will of God.

(Romans 8:22-27)

i am bloody cries

of women

forced onto boats

bound

for the promised land

of freedom

i am the deafening silence

of thousands of years

of history

tradition

culture

family

manhood

out of earth and water

and earth unnamed

voices moaning

in a struggle to survive

beaten down into the soil

the seed

that grows a nation

my God is not the white man’s god

i am not here for money

i do not seek fortune

i am not an immigrant

i am not an object

i am not your pot of gold

i am a man

a woman

a child of God

to God i cry

as my feet beat

the ground

my hands

my body

a table

a chair

the floor

i pound

crazy rhythm

like the caged animal

that i am not

can you hear this

know this

hear this

see this

as freedom

where is freedom

happy darkies

singing and dancing

a survival show

revival show

a sold out show

old black joe

and uncle tom

there are no happy darkies

there are only desperate

men and women

crying to my God

not the god

$$$$$$$$$$$$

for freedom

crying to my God

for freedom

‘my God my God

why have you forsaken me’

i am call

and response

i am screaming

met with

silence

scream

silent

unnamed voices

workin’ & moanin’

the unknown

i cannot tell

juba man

pattin’

a guitar?

a banjo?

a fiddle?

juba man

pattin’

singin’

always singin’

n@#$%^s always singin’

‘cause they are happy

not happy

not singin’

for you

singin’

for my

people

this is not a minstrel show

this is music

this is art

ma

ma

raining

music

down

singing

‘cause that’s a way

of understanding…’

now

i got my hands on a piano

harmonic conception beyond imagination

rhythm beyond belief

i see you

in my hands

i see you

horowitz gawking

rubenstein fawning

you denying

this

art

tatum jr

i am a royal heir

to black, brown and beige

fantasies of a real

duke

praying

‘look down and see

my people through’

look down

i am here

beaten down

but i look up

i see a bird

soaring above

the sound

the sound

of sax

and trauma

i am miles away

the muted voice

of a grown man

brutally beaten

by police

for loitering

under a marquee

a marquee

bearing

my

name

my name

my name

is

Bessie-Ella-Mahalia-Marian-Sarah-Carmen-Abbey-Nancy-Chaka

Lady

Day

dawning

on the [strange]

fruit

trees

of

alabama

my name is pops

i am black

and blue

as bud walks in

i am saying “goodbye…”

to the president

i hear

the trane

approaching

with great

big

giant

steps

bounding

through

interstellar

space

dear lord

i

just

want

to

talk

about

you

for

your

love

is

supreme

Jesus keep me

near the cross

this is not your minstrel show

this my music

this my art

this my life

my life

indispensable

undeniable

incredible

sights

and

sounds

spiritual

ame-cme

thomas d

baptocostal-cogic

frenzy

i am

albert ayler

eric dolphy

ornette coleman

cecil taylor

julius hemphill

oliver lake

david murray

hamiet bluiett

roscoe mitchel

don cherry

lester bowie

dewey redman

don byron

archie shepp

william parker

rashied ali

and

charles gayle