EXPERIENCES

In this section I describe and explore two leadership experiences in my early teaching career – one at Hayes Memorial Adventist School and the other at the Rothbury School. These experiences serve a central role in this autoethnography as story, data, and touch points for analysis. Additionally, as is often the case in autoethnographic research, the experiences prompt reflective performance of identity. In this case those performances are literal performances of poetry, music and visual art. Those performances are simultaneously data, analysis, representation, knowledge and embodiment of my identities and understandings of relationships and cultural interactions.

Experience: Hayes Memorial Adventist School

I was hired as a part-time band director for Hayes Memorial Adventist School, a suburban, Seventh-day Adventist junior high school. Most of the students’ families hail from white middle class or working class backgrounds. I think I was hired because of an unplanned vacancy in the band director position. I was initially called to sub for the band teacher. I subbed for a couple months. The band teacher never returned. I don’t remember being interviewed for the position or anyone ever asking to see my resume or credentials. I was asked if I would like to take the position as the band teacher. I said, “yes.” That was that. There I was.

Three years later I was preparing for my last concert with the symphonic band. There were just over twenty students in that ensemble. They were the older, more mature players. I also directed the concert band, with younger students, mostly fifth and sixth graders. The symphonic band was supposed to be the best group. There I was with the best group that was not so great, preparing for a concert for which I did not have sufficient material.

I did not have sufficient material because most of the band material that I had encountered to that point seemed to me to be culturally irrelevant, objectionable or technically out of reach for the students. There were a few popular pieces in our repertoire, such as the Mission Impossible and Star Wars themes, that we had overperformed by that time. Other choices were military marches or themes from the larger repertoire for concert band. Both of those choices lacked appeal to my taste and sensibilities, first, because they were too white (my father would definitely disapprove of that sort of music) and second, because that sort of music did not fit my own image of what a jazz avant-garde artist ought to perform. As a consequence, I found myself facing an upcoming concert with no clue as to what music the band would perform.

That did not seem like a terrible dilemma. After unsuccessfully auditioning a few pieces from the school music collection, it occurred to me that suitable music for the program might actually be easy to come by. The band could play free music. It would be liberating and fun for the students. For me, it would mean getting to what I knew best, my musical roots. I was really excited about the possibility of leading the group in the free music.

So there I was. I did not know that I was preparing for my last concert. But there I was, preparing for my last concert. I was genuinely excited. I remember the last rehearsal. It was a difficult rehearsal. In the rehearsal I told the students to “just play.” I motioned them to start playing. I think I had a baton. I gave a huge enthusiastic downbeat. Nothing! No sound! No one played a note.

I explained what should happen. Play freely and soulfully. Give it everything you’ve got. Just play and whatever comes out of the instrument is fine. Have fun! Spontaneous creation.

So I went back to the podium and motioned for the group to set themselves to play. I gave a big preparatory motion and hearty downbeat. And this time there was, at least, sound. Several of the young players started reading whatever score happened to be in front of them. The rest of the group sat silent. I stopped.

By now a bit of frustration was setting in, both on my part and on the part of the students. I imagine that they sensed my frustration. And looking back, I think I was unmindful of the fact that many of them were very eager to please me (or any adult or authority figure). Perhaps they were experiencing shame or embarrassment that they were not doing what I wanted. Did they trust me? I was thinking that they were not trusting me enough – not enough to let go and just play their instruments.

My next demand was that they turn the music stands so that they faced the podium. Some of them turned them right away. It was not happening quickly enough. I started turning stands. Don’t look at the scores. This needs to be done without looking at the scores. In a rushed and exasperated posture, I gave another downbeat. This time there was more sound. It was not great. But for about 30 seconds or so they were actually playing freely.

I think the free playing was not to their liking. I don’t remember there being any excitement or even cautious enthusiasm about what had just taken place. Let’s do it again. By now they had started to understand what I was asking. They played. You could hear them playing some of the melodies, the parts that they had memorized from our “standard” repertoire. They were not really freely improvising. I think they probably figured that if they at least played something, anything, it would ease the tension.

That was our last rehearsal. There should have been more rehearsals. But, of course, I did not believe that rehearsal was a good thing. It was better to “just play” – let everything be in the moment. Don’t spoil the potential of spontaneous beauty with rehearsal. That is what I had been taught. That is what I aspired to. I believed, and still believe to some extent, that rehearsal is often overdone.

I remember the concert in the school gym – it was awful. We were not prepared to do the experimental pieces when we went in. We played a few songs off the charts. Then I told the students to put their sheets away and “just play.” The “free” song was listed in the program as “Tune Up.” I thought that would be exciting and liberating for them, something they would feel good about. It went horribly. The kids froze. They did not know what to do. When I gave the downbeat some students played timidly and softly. They again reverted to some of the lines that had been memorized from other songs. Many students just sat holding their instruments as I waved my arms more and more vigorously, trying to encourage more sound production. To say the concert was not well received would be generous. I remember hearing the kids say about the band, “We suck.” In hindsight, I can see that there is no reason why they would have known what to do. They had never in any of their experiences thought about or been asked to, or shown how to play freely – the language of free jazz or even experimental Western music of any sort appeared nowhere in their cultural experiences, either individually or collectively.

That concert was in mid-March. I am sure it was just weeks later, before the end of April, the school principal called me into the office. The conversation went as I expected. The students were dissatisfied. Parents were dissatisfied. I was told my contract would not be renewed for the following year – I was fired.

Objectionable Music

Reflecting on that experience at Hayes, one thing that stands out is the band music. In my notes, I wrote, “the band music is objectionable.” The fact that I did not like and/or could not identify with the band repertoire was because it was not “cool” (culture) and it was not Black or hip (it would not meet my father’s approval). I have no connection with that music, it does not resonate with me. And it is the band repertoire, not the orchestra material, as we shall examine later. The orchestra repertoire is just fine. What is it about the band music? For me the band music did not seem “cool” and that was a big part of why I did not feel comfortable leading that music. Being cool doesn’t just mean being stylish or popular. One of the most important aspects of cool is its function as a site of resistance to injustice and oppression (G. Cross, 2010; Dinerstein, 2017). Among Black people, cool was originally a way of not reacting, at least outwardly, in a manner that matched the atrocities to which they were subjected in white society (Jones, 1963). And cool continues to have such meaning today for me. Moreover, cool is part and parcel of jazz leadership. Cool is, perhaps, one of the paradigms that has not been advanced in prominent leadership theories. Nonetheless, cool, “through a jazz viewpoint,” is an important factor that underlies Black male leadership (G. Cross, 2010).

The connection between cool and Black male leadership is important to my own practice. For myself, as a Black male, jazz avant-gardist, I could not see a way to direct the standard band repertoire and maintain the “cool” resistance to the oppressive exclusion that I had experienced in undergrad days and felt like I was still experiencing at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. It seemed as if one way that I could maintain a sense of dignity, via coolness, was to have the students play the music with which I was most familiar and that I was sure was sufficiently “cool.”

“Just Play!”

If coolness is a mark of Black male leadership via jazz culture, there is another part of jazz culture that I brought into the experience at Hayes Memorial, namely, “just play.” Stefon Harris (2011) expresses that jazz ethos perfectly when he starts the following performance with a statement “I have no idea what we’re going to play. I won’t be able to tell you what it is until it happens.” What follows is a collective free improvisation with Harris and three other musicians. This is an excellent example of how “just play” works.

(TED, 2011)

Harris (2011) goes on to posit that “There are no mistakes on the bandstand.” In other words, everything that happens as we “just play” can be thought of as an acceptable, if not desirable, part of the experience. “The only mistake is if I am not aware, if each individual musician is not aware and accepting enough of his fellow band member to incorporate the idea and we don’t allow for creativity" (Harris, 2011, sec. 10:11).

The idea of “just play” is how I had learned to play. It is the method that I and so many other musicians had come up with. It was part of my creativity and culture. I was trying to encourage creativity in the students at Hayes. This is a tradition in jazz music, a kind of cultural and pedagogical component of the music.

T. S. Monk, son of the jazz master composer, pianist and bandleader, Thelonious Monk, reflects on his beginning to perform in his father’s band:

“I just started playing with the band, but I’d known from observing him that [Thelonious, the elder] wouldn’t say anything…Thelonious was from that generation that, you know, you were supposed to be playing all that hip stuff. There was something to say if you weren’t, but if you were, there really wasn’t anything to say because that’s what we do" (Monk, 2011).

Guitarist Jody Fisher (in conversation with guitarist George Benson): “Lots of time people weren’t that helpful. I remember getting up on stage, people would start a tune. They wouldn’t tell me what key we’re in. They wouldn’t tell me what tune we’re doing. They wouldn’t count it off and they just expected me to sink or swim" (MBP, 2021).

Guitarist Russell Malone (2022) his experience with jazz master, George Coleman:

Playing with any of the masters is always a great experience. We’re all trying to learn and get better, and they still have so much information to share, and a lot of lessons to teach. Jazz master George Coleman is still taking us to school. And when you play with him, you never know what tune you’re going to play, or what key it will be in, because he doesn’t tell you anything. You just have to jump in the frying pan and cook. You might walk away beat up and bruised a little, but you also walk away a better musician. That’s old school, and I love it. (Malone, 2022)

I remember having a similar experience with my father in a recording session. We all arrived at the studio, my father (tenor saxophone), Juini Booth (bass), Michael Wimberly (drums), and myself (piano). There was no conversation about what we would play. It is almost as if there had been a conversation, it would have ruined the music making. Even after setup and getting levels, there was no mention of what we would actually play, no melody, no form. The only guidance from my father came in the form of this admonition to all the players: “If anyone breaks a sweat, they are fired!” Then we were playing.

It is that kind of sink or swim pedagogy and leadership with which I was most familiar. While it is true that I had experienced different models and methods as an undergraduate music student, none of those methods had registered with me as effective or desirable. They were from a different culture, a different tradition – a tradition and culture that seemed very “uncool” to me. My understanding was that the individuals whom I admired as great leaders of great music, and most of the great musicians whom I admired, had espoused and championed the “just play” method. To my understanding, that was how great music was made and I was determined to use that method in my leadership.

In hindsight, I believe I should have had some sort of chart for them to follow. I also could have been more patient and encouraging. At that time I did not understand that they had absolutely no frame of reference for what I was asking. But what did I know? My understanding was that by virtue of the fact that they had an instrument meant that they had experimented with the variety and range and tonal possibilities that the instrument offered. I thought that surely because their parents had provided the musical instrument, they (students) had been encouraged to test all the possibilities for playing an instrument. My assumptions and questions were along the lines of what Hickey (2009) asserts: “Children come to us as eager improvisers and experimenters. How might schools and music educators capture this proclivity and encourage and nurture the disposition?" (Hickey, 2009, p. 296). I believe that as a teacher and leader, it would have been better for me to provide some sort of building block or scaffolding for the students to practice free improvisation, a practice of which they had little or no knowledge or skill (de Bruin, 2019; Powell & Burstein, 2017; Selby, 2022).

Liberation, Freedom, and Free Music

As a music leader at Hayes I thought being liberated from the “white man’s” oppressive music rules was the most important thing that a musician could attain. I wanted liberation not only from the oppression of the white musical forms but also, and perhaps more importantly, the oppression of the disposition to exclude and demean Black music. As Jones (1963), “Negro music is the result of certain more or less specific thinking about the world" (Jones, 1963, p. 211). So in my mind, liberation from all of that was the best thing that I could bring to my students. And even though I never explicitly spelled things out in those terms to the students (I was ignorant but not that ignorant), those thoughts of breaking away from the “oppressive” band repertoire was exactly my intention.

Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones)(1963) writes:

It was the generation of the forties [young jazz musicians] which, I think, began to consciously analyze and evaluate American society in many of that society’s own terms (and Lester Young’s life, in this respect, was reason enough for the boppers to canonize him). And even further, this generation also began to understand the worth of the country, the society, which it was supposed to call its own. To understand that you are black in a society where black is an extreme liability is one thing, but to understand that it is the society that is lacking and is impossibly deformed because of this lack, and not yourself, isolates you even more from that society. Fools or crazy men are easier to walk away from than people who are merely mistaken. (Jones, 1963, pp. 184–185)

Reflecting on Baraka’s (Jones’) point in connection with my own experiences, I have always felt that “it is the society that is lacking” both of American society generally and Adventist society in particular. I have understood that the impetus for free jazz musicians, in terms of their social and musical motivations to break free from established traditions, came from the “boppers.” I have only ever heard my father and the musicians of his generation speaking in the most glowing terms of Bird, Dizzy and Monk, even though those same “boppers” might not have warmed to the free jazz movement. The free jazz people held the boppers in the highest regard as liberators of the music and as champions of social justice.

Describing the work of Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman, Jones (1963) postulates that they “restore to jazz its valid separation from , and anarchic disregard of, Western popular forms.” From my earliest days, that is what I understood jazz music, particularly the jazz avant-garde to be, a deliberate, if forceful, departure from the Western canon and a statement on the role of Black music as representative of leadership in intellectual and creative domains.

Why would Seventh-day Adventist junior high school students want to depart from the Western canon? I have not seen any evidence to suggest that they would want to depart, except in cases where there is a theological or doctrinal disparity between what Seventh-day Adventists officially espouse and curricular materials. For, example, even though the Seventh-day Adventist church in North America recommends use of McGraw Hill “Spotlight on Music” Grade 3 and Grade 5 music textbooks, the “Utilization Chart[s] for Spotlight on Music Lessons” published by the North American Division of Seventh-day Adventists (North American Division of Seventh-day Adventists, n.d.-a, n.d.-b) recommends omission or modifications of any materials that involve jazz, rock, latin, or dance musics. In one noteworthy recommendation, the Grade 3 utilization chart specifies “omission” of the urbanization protest song, “Big Yellow Taxi”; the guide identifies the song as “inappropriate" (North American Division of Seventh-day Adventists, n.d.-a). Even more salient to the present study, other recommended omissions include “Singin’ the Blues” (“Song styles not encouraged”) and the “Compare Syncopated Rhythms” lesson (North American Division of Seventh-day Adventists, n.d.-a).

From such an examination of the elementary music curriculum, it becomes clear that my attempt to introduce a free form, jazz style into the program was misplaced, if not misguided. Had the school been a predominately Black school, there might have been a chance of at least a passing familiarity with Black music idioms. However, in the predominately white, conservative environment of Hayes Memorial there was little to no chance that jazz avant-garde inspired programming would gain traction. I am unsure whether my ignorance of that fact was intentional, unintentional or some combination of both. I am, however, certain that I wanted to share with the students at that school the joy and liberation of free music making.

Holy Ghost (Ayler, 1965)

It seems to me that playing freely is the ultimate expression of the soul of the musician. At the same time, if the music is so free that it is not recognizable within the context of known structure (s), the artist or another knowledgeable person should interpret the music. Otherwise, it would be unintelligible and not particularly beneficial to anyone other than the artist. (see 1 Corinthians 14). It has been my experience that within church circles it is typically not enough to say, “let the music speak for itself.” An explanation is required, at least for the Seventh-day Adventist audience, to facilitate the process of sense-making of the music.

When I was at Hayes Memorial Adventist School, apart from the fact that I was a Black male jazz avant-garde musician, I did not have a clear explanation or representation of the intent for playing free music. My only explanation was that the jazz avant-garde was my identity and I was doing me. I knew the history of the music. I could explain the history. However, that history was hardly relevant to the audience at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. Not only were they unfamiliar with and without any direct connection to that history, they were firmly part of a tradition that regarded jazz as undesirable, if not entirely anathema. As such the situation in which I found myself at Hayes Memorial Adventist School was precarious at best. As a Black male jazz avant-garde artist intersecting with Seventh-day Adventism I was not adequately prepared. Perhaps more importantly, I did not adequately reflect on the circumstances and plan a reasonable course of action to either systematically advance free music in the Hayes Memorial Adventist School cultural context or recognize the misalignment of my identity with the culture and seek a different position.

Authenticity and Intersectionality

Reflecting on my identity and the Hayes Memorial Adventist School situation now, I see much more clearly how playing improvised music soulfully is not only an expression of the self but it is also a cultural expression. More specifically, I was an outsider attempting to express a culturally infused music in a culture that was not welcoming of such an expression. What was not as obvious to my younger self was that the intersection of self and culture, especially when the self and culture are in ideologically different places, can have weighty consequences.

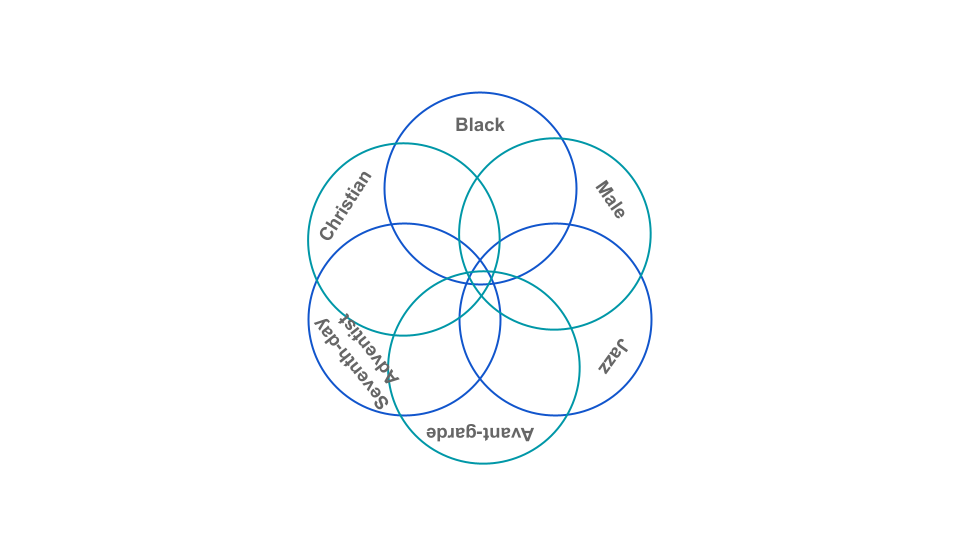

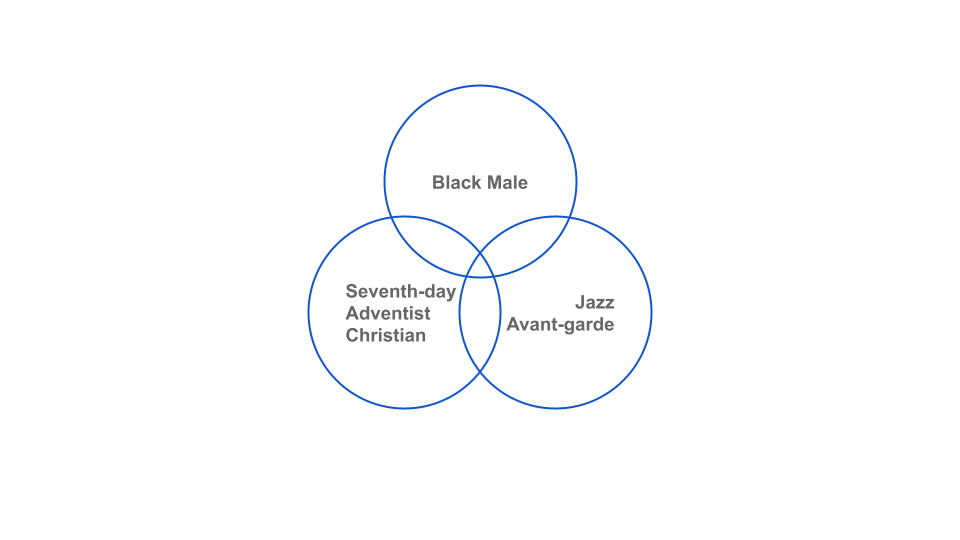

For me the consequences were not being able to live authentically at the intersection of Black maleness, Seventh-day Adventist Christianity, and the jazz avant-garde. From a reading of Trilling (1972) the concept of authenticity, being true to self, emerges from his thinking about sincerity, being true to others. Lindhom (2008) extends the views of Trilling into cultural spaces such as visual art, music, market economies. and group identities. Lindholm suggests that in Western societies authenticity is applied not only to the human self but also to things to the extent that they are commodified and marketed for pleasure and gain (Lindholm, 2008). In the experience at Hayes Memorial Adventist School, I see myself questioning whether I am living authentically as a Black male, authentically as a Seventh-day Adventist, and authentically as a jazz avant-garde artist. To be clear, this is not about how I am representing myself or how others perceive me; those are concerns of sincerity, which might be an interesting study but it is not applicable here. I believe that when I consider any one of those identities, Black male, Seventh-day Adventist, or jazz avant-garde, in isolation, I can honestly say that I was being true to myself. However, throughout the Hayes Memorial Adventist School experience, I thought only about one identity at a time. It was not until this present study that I thought about what it meant to be true to myself at the intersection of all three identities.

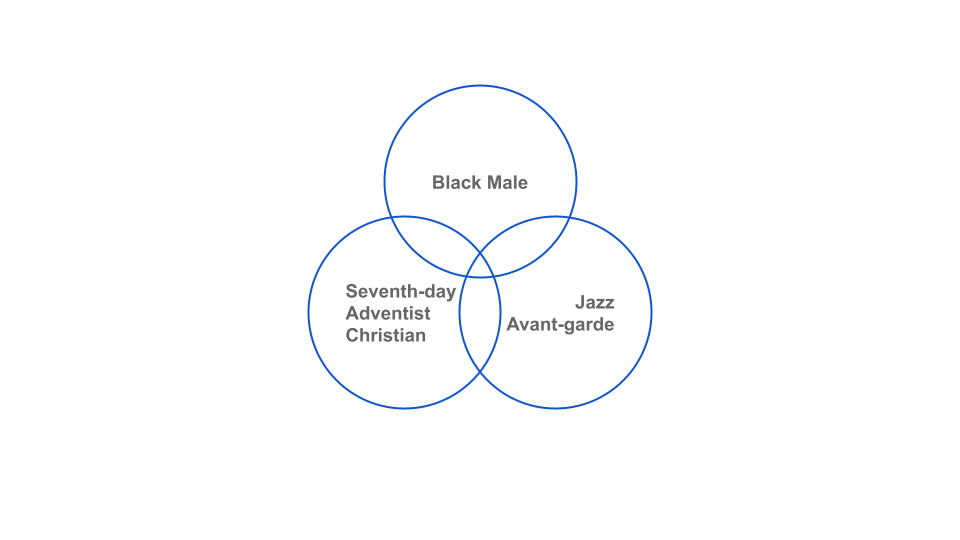

As a preamble to probing my sense of authenticity at the intersection of Black male, Seventh-day Adventist, and jazz avant-garde identities, I will first acknowledge that I am narrowing down to three what could be understood as six identities. First a view of intersection of the three identities:

A view of the six identities at intersection,

present intriguing complexities. However, thorough interrogation of those complexities is beyond the resources of this study. Consequently, in my reflections I merge the Black and male identities, the Seventh-day Adventist and Christian identities, and the jazz and avant-garde identities. Again, those three identities at intersection:

As mentioned above, when I thought about whether I was authentic in any one of those identities, I was certain that there was little or no incongruence in who I thought I was (e.g. as a Black male) and who I actually was. However, when I thought about whether I was authentic at any given intersection, I was less than certain. As I thought about what was happening, it occurred that I was thinking about one way of being but behaving in another way. For example, when I think about or conceive music, it is almost never in Western classical terms. The musical conceptions in myself are almost always Black male and frequently they are both Black male and jazz avant-garde. However, whenever I am in the company of Seventh-day Adventists, I most often perform a version of myself as a musical artist informed by generic musical ideas that encompass all the major Western traditions. Thinking a bit more my experience at Hayes Memorial Adventist School, I realized that I was operating in a space that DuBois (1904), and later Fanon (1952; 2008) refer to as “double consciousness” – the plight of Black people in white society.

This epiphany about double consciousness made clear that I was looking at myself both as I saw myself but I was unable to perform as I saw myself because I was also looking at myself as I thought others saw me. That view prompted feelings of inadequacy, aptly expressed as “measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity" (Du Bois, 1904, p. 3). I felt that inadequacy most keenly in the presence of white Seventh-day Adventists. I knew that the Black experience in the Seventh-day Adventist church was fraught with peril (Dudley, 1997, 2000; Graybill, 1971; Rock, 2018) and even death (Baker, 2020). Further, as mentioned above, the church has not been especially welcoming of jazz music or other music that departs from the sterile European cultural forms to which it subscribes. Consequently, I did not feel that I could be my authentic Black male, jazz avant-garde self in Seventh-day Adventist society. Nonetheless, I felt compelled by my religious belief and, at the time I was working at Hayes Memorial Adventist School, by a need to provide for my family to be productive in the Seventh-day Adventist church. I was caught in a double consciousness of my own identity and the identity that I believed others ascribed to me – an unsatisfying situation, to say the least.

Continuing to explore the authenticity crisis that I experienced, I turn to another writer who takes cues from Trilling. Rebecca Erickson (1995) discusses authenticity from a structural interactionist perspective, positing that authenticity, like identity, is constructed by way of exchanges between the self and society. Erickson draws a conclusion that marginalized people frequently must confront a choice to either be true to “self-values” or meet the “expectations of powerful others" (Erickson, 1995, p. 138). Using examples such as “white and female” and “Black and middle-class,” Erickson connects authenticity and identity with an observation that people have multiple identities that should not be viewed in isolation; rather, those identities should be understood as working together (1995, p. 136). The points Erickson makes resonate with me and my experience. Those points are examined independently from Erickson and more fully by scholars who examine identity through the lens of intersectionality.

Briefly introduced above in discussion of vision of leadership/beginning the research, intersectionality “investigates how intersecting power relations influence social relationships across diverse societies as well as individual experiences in everyday life" (Collins & Bilge, 2020, p. 1). Intersectionality was originally articulated as a lens for understanding and deconstructing legal and social frameworks that harm women of color (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). Intersectionality has also been used to examine race, class, gender, ability and other social constructions.

Thinking about the identities (racial/gender, religious, musical) I am studying in this research, intersectionality has been suggested and used as a frame for viewing Black males in society, particularly with respect to incarceration and health care (Carbado et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2018). Intersectionality has proven useful as a vehicle to investigate a religious identity along with a variety of other identities, including Muslim women (Bilge, 2010), and the LGBT community (Ciobotaru, 2020). Singh (2015) uses the agency of religious women as a space to critique intersectionality, arguing that intersectionality is based on a “negative consensus” on oppressive structures that does not do justice to the aims of feminist dialogues of religious women’s agency. In one study that shares at least a loose connection to this present work, LaShonda Anthony (2013) found that intersectionality was one of the best ways to understand the experiences of Seventh-day Adventist college students. In the field of music, intersectionality has been applied widely to issues of race, gender, and sexuality (DeCoste, 2017; Hudson, 2021; Koskela, 2022), to hip-hop music and culture (Collins & Bilge, 2020) and, of particular interest to me, the jazz avant-garde (Buffington-Anderson, 2022) via the Black Art Movement (for a discussion of the relationship of the Black Arts Movement and the jazz avant-garde see Robinson (2005) The Challenge of the Changing Same: The Jazz Avant-garde of the 1960s, the Black Aesthetic, and the Black Arts Movement).

Looking through an intersectionality lens, I gain insight into the way I interacted with society via the Hayes Memorial Adventist School culture. Both the school and the larger church as institutions were an authoritative power structure that I had to navigate. I had a sense that as the only Black male teacher in the school, my work might be scrutinized more closely than might be the case for a white male teacher. Even with that sense, I did not feel a great deal of tension around authenticity about Black maleness – I had become used to being the only Black male in many situations throughout my educational career and I had become adept at code switching (i.e. changing speech and language patterns to fit into white contexts)(Boulton, 2016; L. W. Nelson, 1990). In that sense, I had come to terms with the double [linguistic] consciousness. However, when confronted with the situation of being expected to perform as a Black male, Seventh-day Adventist musician, the intersection of those identities, juxtaposed to what I considered to be an oppressive system of music education, made me feel that I would not be comfortable with myself – I would be inauthentic – if I did not bring the jazz avant-garde into the classroom. I wanted, both for myself and for the students, to deconstruct the narrative that music has to be structured in the Western classical tradition in order to be valuable or authentic.

Unfortunately, I never publicly self-identified as a jazz musician at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. I felt that if I had done so, it would have jeopardized my employment. Consequently, whenever I played an instrument, I played cautiously, not branching into real freedom or even an improvisational style that could be characterized as jazz. Whenever I improvised, I used European classical references and devices. In other words, I tried to whiten my music. That felt terribly inauthentic. And I am sure it also sounded bad because I never played confidently. Essentially, I was masking my true self. Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote of this circumstance more than 100 years ago. It seems to me that there has been no appreciable change:

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties,

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask!

(Dunbar, 1895)

As a novice teacher/leader at Hayes Memorial Adventist School, I felt that there was a possibility for me to be authentic in leading the students into new ways of experiencing and understanding music making. Not long after that last concert, I knew that I had misjudged the possibility. There was not really a space in the school culture for a serious approach to music making via the jazz avant-garde. Consequently, there was not a place for my authentic self. Moreover, I had not developed the knowledge or leadership skill to scaffold or incrementally negotiate the creation of such a space. That being said, given the conservative culture of the school and the historical position of the Seventh-day Adventist church on jazz music, I wonder if scaffolding or negotiation would have been fruitful or possible, even if I had possessed that knowledge and skill.

So the interaction with the culture at Hayes Memorial Adventist School (and likely with the Rothbury School - but I have not arrived there yet) has to do with the interaction of a Black person in society – a Black person who knows that authenticity is all but impossible because Black people do not have the privilege of fully living out identities that are entirely of their own making, or even living their identities out as fully as people in the dominant class.

I characterize my musical experiences at Hayes Memorial Adventist School as mostly a failure. I was challenged by being unaware of school culture. I did not belong at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. There was, perhaps, an assumption by all parties that I did belong and shared the same culture and belonging because of my Adventist identity. There was never any mention of race, my Blackness or their whiteness (privilege). Yet my culture was conspicuously absent – as it had been when I was in undergrad studies. That felt suffocating. Perhaps, that is why I was so eager to perform experimental music. That might have been a way to inject my culture. Clearly, that was a clash of cultures that did not end well.

Experience: The Rothbury School

Immediately after being fired from Hayes Memorial Adventist School, I searched the newspaper for teaching positions. That search led me to answer a help wanted ad for the position at the Rothbury School. After two interviews, I was hired as a part-time orchestra director for the Rothbury School, a private, suburban middle and high school. Most of the students’ families are from white, upper class or upper middle class backgrounds. My initial responsibilities were to conduct the orchestra, teach beginning guitar and recorder, and plan and lead student musical performances for weekly chapel services, mainly with the orchestra or members of the orchestra. The Rothbury School was a religious institution, though not in the Seventh-day Adventist tradition. After working at the school part-time teaching music for two years, teaching religion was added to my responsibilities and I became a full-time faculty member.

In the spring of my fourth year at the Rothbury School, I was preparing for a chapel service with a theme of experimental music. The featured pieces for that service were as follows:

Adagio from an Oboe Concerto in C Minor by Benedetto Marcello

Evening in Transylvania by Bela Bartok

Lo and Behold by Michael Gayle

Soundscape #57 by Michael Gayle

The last work in that list, Soundscape #57, is very important to me. It represents a high point in my musical and teaching career. As I reflect on it now and as I reflected on it then, that composition stands out as a success for me as a Black male, Seventh-day Adventist, jazz avant-garde artist.

The repertoire for the Rothbury School orchestra came mainly from the Western European and American classical tradition. The orchestra performed works that were either written for or arranged for small chamber ensembles. We played pieces by Bach, Handel, Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, and many other classical composers of varying degrees of fame. I did most of the arrangements myself, to fit both the instrumentation and range of capabilities and skill levels of the students. When I started there were five students in the group. Five years later that number had grown to twenty regular players, with more for special occasions. In addition to the “standard” repertoire, I wrote original studies and compositions for the students. I wrote music for band, orchestra, dance and individual students. Those original works were designed to help the students grow both musically and personally. I lived music and tried to teach my students to do the same – to live the giftedness that you have.

During my time at the Rothbury School, I had been working in my own thoughts about creating visual scores. I had also been experimenting with programming and deploying computers and using applications to musically “perform” a picture and to create visual images while performing them at the same time.

One of the ideas that I landed on was drawing pictures using software and having live humans perform the pictures. After some personal experiments, I decided to do some experiments with drawing pictures and performing them with students at the Rothbury School. The orchestra had been working on some “experimental” scores that used traditional notation, particularly Lukas Foss, Aaron Copeland and some scores that I had written. It seemed like performing pictures would not be too much of a stretch for the students.

I drew the composition picture but did not immediately share it with the students. Instead, in the first “rehearsal,” we discussed the concept of using something other than traditional notation to guide the performance. My experience at Hayes Memorial Adventist School suggested that if I asked the students to “just play” without any sort of visual reference, things might go badly. Consequently, after discussing alternatives to traditional notation, I drew a single curved line on the whiteboard and demonstrated at the piano a musical interpretation of the line. Next, I asked the students, in ensemble, to play the line as I conducted the start and stop of the playing with hand gestures. They started playing tentatively. I could hear some students playing a major scale in one direction or another and stopping because they did not have another idea of what to play. Other students held a single note while varying the loudness (dynamics) of the sound. Everyone tried something. And that they tried was, literally, music to my ears.

At the next rehearsal I introduced the students to free playing without any visual aide. It would probably be better to say that I “engaged” the students in free playing. They all had, on some level, been introduced to musical and other forms of artistic improvisation, the school had a top-ranked jazz band and also dance and theater programs that employed improvisatory and experimental techniques. Moreover, many of the students lived in families and communities where the arts of all sorts were part of their cultural experiences.

First, I explained what the expectations or non-expectations were for free playing. I demonstrated options including using the full range of the instrument, randomness, motif development, and variations of tone and dynamics. Next, I led the students in some guided practice of several devices. For example, we played random notes then played a sustained pitch, selected randomly, and varied the dynamics of that sustained pitch. It seemed that the students were enjoying the opportunity for free expression.

Also, during the second rehearsal, I introduced the students to the Alesis AirFx. The AirFx is a theremin-like instrument that responds to hand gestures to create pitch and sound variations – demonstrated here by John Schussler:

(Schussler, 2021)

The Alesis instruments are based on an instrument invented in the early twentieth century by Lev Sergeyevich Termen, also known as Leon Theremin (Glinsky, 2000). Here he performs with the instrument that bears his name:

(slonikyouth, 2008)

The students enjoyed experimenting with the AirFx. I believe it opened their imaginations to a realm of possibilities that they had not previously considered. From that time forward, there were a couple students, a bass player and a pianist who wanted to play the AirFx every time they came to class.

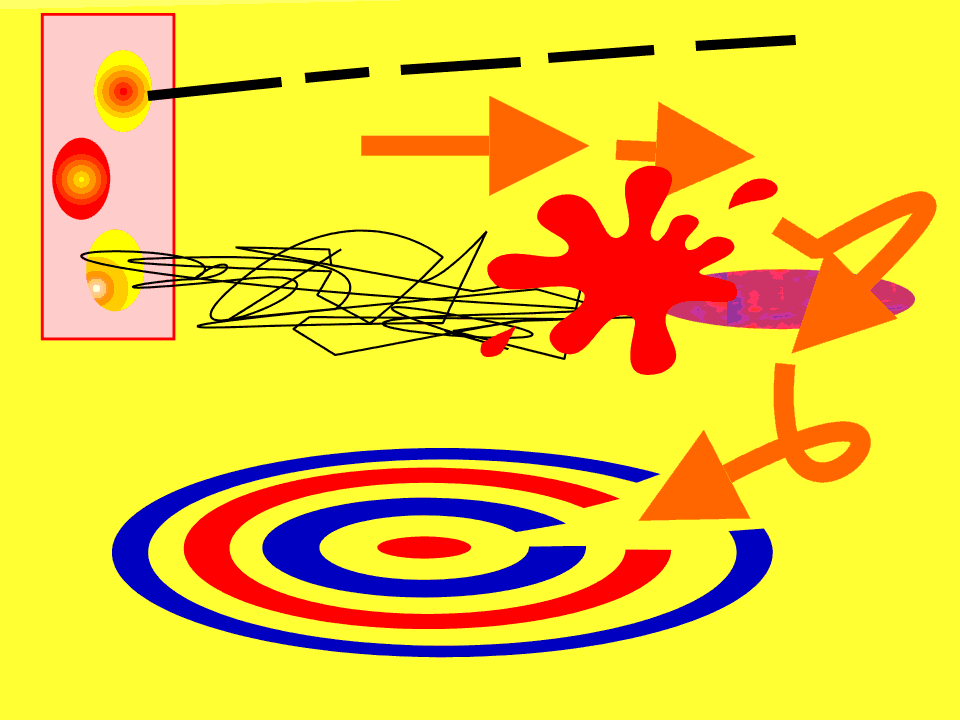

The students had multiple opportunities to play and experiment. After a week or so of experimentation, I introduced the “full score” of Soundscape #57 as seen here:

The area that looks like a target was, I believe, inspired by the unsuccessful attempts to perform free music at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. The target, along with the lines and arrows, is meant to provide a kind of grounding for students to think (and play) with direction and intent. It was that direction and intent that was missing from the experiments with the students at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. I did not provide an opportunity for the Hayes Memorial Adventist School students to explore foundational purposes or intents for the music. Consequently, I imagine that it felt to them as if they were being thrown into chaos without any rhyme or reason.

With the full score in view and practiced approaches to free playing within reach, the students rehearsed Soundscape #57 along with several other experimental pieces over a period of about two weeks. We agreed that the approach to the piece was that they could select any parts of the piece for performance. We also agreed that the score would be projected on a screen so that the audience could see the same thing that we were seeing. That view would make the music more approachable, if understandable, for the audience. Over the two weeks of rehearsal, the students' confidence grew and their sound improved considerably.

There was no small amount of excitement and anticipation on the Tuesday morning of the performance. We had set up and rehearsed in the auditorium the day before. All the technical pieces for sound reinforcement and visual projection were in place.

The program began with me speaking. I introduced the program: “Good morning. This morning we will go on an adventure. Our music is brought to us by a group of bold and courageous musicians, who you otherwise know as our orchestra. The sounds that you will hear this morning will be, I’m sure, somewhat strange. You will see some things that you have not seen before. You will see visualizations of the music projected onto a screen. You will see, for maybe the first time here at the Rothbury School, an actual score [projected] so that you will follow that. I am sure that you will enjoy it. So sit back and soak in the blessings of God this morning.”

The program continued with:

Adagio from an Oboe Concerto in C Minor by Benedetto Marcello

Congregational singing of Lord, I Lift Your Name on High

An invocation

A prayer of blessing

A reading from the Book of Isaiah

Evening in Transylvania by Bela Bartok

A responsive reading of Psalm 111

Lo and Behold by Michael Gayle

A reading from the Book of John

A homily by a student

I was surprised by the homily. The subject was “passion.” And unknown to me, I was the subject of the introduction. The student began:

I don't remember the first time I saw it. It could have been in ninth grade. Maybe, I just didn't pay as much attention. But now I get excited every time. Many of you have seen what I'm talking about, probably today. And if you haven't, it is now a new graduation requirement – no senior lounge without it. You must at one of the orchestras concerts, [turning to me: and I hope you won't be embarrassed by this] watch Mr. Gayle, the instructor and conductor. Now it is easier for those of us in chorus who face him. But if you get the angle just right, you too can see the transformation from eyes closed eyebrows raised, head cocked back, to bending low, head shaking, and violently rasping arms. I admit, I used to smile and say, ‘Doesn't he realize we can all see him doing that?’ Yet now, as I said, I look forward to this display. For Mr. Gayle does know that we see him and doesn't care – for one reason – His music is his passion! That is what I want to talk to you about today, “passion.”

The student went on to make a case for living a passionate life, dedicated to making the lives of people better because of what you do. Several other teachers were held out as examples. And the student concluded by saying that they were seriously considering teaching as a career because of experiences with teachers who were passionate and caring for the best in students.

After the homily, the orchestra performed Soundscape #57. I believe it was one of their best performances of any piece. It ended with a glorious cacophony of passionate musical expression.

The program ended with a prayer led by the school chaplain.

This experience seems like a great success – not so much because of the music – but because of the reception by the students and the audience. Following the performance, there were many congratulations. At the end of the recording, after the prayer of benediction, my voice is heard speaking to the orchestra – I said, “Marvelous!” By contrast to the Hayes experience, I left the school a couple years later, entirely of my own volition, to pursue graduate studies.

Writing Freedom and Slipping In

Considering all the emphasis that I had placed on just playing, it seems ironic that a major part of my experience at the Rothbury School was writing. Most of the writing was in the form of creating arrangements of musical works for the instruments and appropriate skill levels of the students in the orchestra, guitar, and recorder classes. For example, in the first year, there were five students in the orchestra class. The instrumentation was oboe, violin, piano, cello, and bass violin. The oboist played at a moderately advanced level, the violinist and pianist played at an intermediate level. The cellist and bassist were beginners. The use of scores and arrangements from the standard repertoire was impossible for such a configuration. Consequently, I had to arrange music for the group. As the group added members, the arrangements were made to fit the new players and their levels of proficiency.

I also composed original music – instrumental studies and works for performance. Starting with the instrumental studies for guitar and recorder classes, the studies were designed to both facilitate gains in technical skill and to promote interest in music. For the orchestra class, I wrote studies with the same designs. However, the studies for the orchestra students were thoroughly informed by the avant-garde, using extended ranges, unusual or random harmonic structures, and techniques that were characteristic of experimental music. The original works for performance followed the same pattern as the studies, their aim was for students to build skill and expand musical expression. Importantly, the musical writing I did at the Rothbury School was driven by two things that I learned from my experience at Hayes Memorial Adventist School – that I would have to carefully slip the jazz avant-garde into the classroom experience and that the slipping in would have to be scaffolded in order to be successful.

Exploring the idea of slipping in, first it is a matter of personal survival. As discussed above, the feelings of inauthenticity that I experienced at Hayes Memorial Adventist School were, at times, overwhelming. My attempt to bring my authentic self into the teaching was clearly met with harsh challenges and, ultimately, unsuccessful. It occurred to me that if I were to attempt authenticity at the Rothbury School, it would need to be done stealthily. Such stealth is not to be confused with a lack of sincerity (Trilling, 1972); I would not make claims about who I am, knowing that, in fact, I am something other than who I claim. Rather, stealth refers to letting people see who I am without people immediately knowing that they are encountering a Black male, Seventh-day Adventist, jazz avant-garde artist (or perhaps just the jazz avant-garde).

Transparently, it was widely known in the school that I was a jazz artist. And it seemed, to me, somewhat ironic that I was leading the [classical] orchestra while there was a white musician leading the jazz band at the Rothbury School. My assignment was to teach classical music. So I had to slip in the jazz avant-garde. LeRoi Jones (1963) talks about this kind of fitting in: “The negro has accepted 2/4 and 4/4 bars only as a framework into which he could slip the successive designs of his own conceptions…he has experimented with different ways of accommodating himself to the space between the bars" (Jones, 1963, p. 192). In both literal and metaphorical terms, I was “slipping my own conceptions” between the white man’s “bars” at the Rothbury School. I had also viewed other artists, such as Anthony Braxton, as a model in this slipping in. Braxton, who made an early entry in jazz avant-garde music with the Chicago-based Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), went on to work across genres, including recognition in the classical music scene (Lock, 2018; 1985).

I believe my slipping in the music at the Rothbury School was fairly successful. The music was well-received by the students and by the school community as a whole. From a personal perspective, I did not feel entirely inauthentic. Even though there were parts of me that felt that I could be doing more in the name of jazz music, the school afforded me space, time, and resources to explore free music. For example, I was awarded a fellowship that included a state-of-the-art personal laptop, leading edge creative software, retreat time and a stipend to work with other creatives and just experiment. I was also awarded a technology grant to create an electronic music lab and curriculum. The Alesis AirFx and music created with it mentioned above was among the technology artifacts that was borne out of the technology grant. I was hired to teach classical music and I did it in a way that felt as true to my jazz avant-garde identity as possible. A letter from a major donor on the occasion of my departure from the school affirms my feelings. In that letter the donor writes: “[The students] had a very strong learning experience thanks to you, an eye opener to the beauty of classical music.”

I believe that success with free music at the Rothbury School was largely because the student performances were scaffolded by incremental experiences with free music ideas, techniques and material. When the notion occurred that I could introduce students at the Rothbury School to free music, I immediately was brought to reflect on the experience at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. I had made faulty assumptions about the students at Hayes Memorial Adventist School, thinking that because I understood free music to be liberating and the most natural way to approach music learning and performance the students would feel the same way and perform accordingly. I had, essentially, thrown the Hayes Memorial Adventist School students into the musical deep end of the pool with no experience or training and expected them to swim like champions. I was determined not to make the same mistake at the Rothbury School.

Scaffolding Structure and Freedom

If I had consulted the literature, I might have discovered the concept of scaffolding (Close, 1990; Lehr, 1985; Pappas, 1984). In scaffolding, educators use strategies to facilitate student achievement of knowledge and skill by systematically adding complexity to learning without going beyond the capacity of the student to navigate the complexity. Jerome Bruner, the leading theorist on scaffolding, writes: “there is a vast amount of skilled activity required of a "teacher" to get a learner to discover on his own – scaffolding the task in a way that assures that only those parts of the task within the child's reach are left unresolved, and knowing what elements of a solution the child will recognize though he cannot yet perform them" (Bruner, 1960, p. xiv). But I did not consult the literature. I knew nothing about Bruner. However, it came to my mind that I should somehow work through a gradual process with the students, introducing successively more complex music concepts and techniques that would lead to free music performance.

Consequently, over a period of several years, I gave the students a few bits of structured, prescriptive conceptual material that was largely experimental in nature. I allowed the students to test and become comfortable with unfamiliar melodic and harmonic forms (e.g. Bela Bartok) and experimental forms (e.g. John Cage and Lukas Foss). Gradually, I introduced music with less formal structure, beginning with recordings and demonstrations of free and so-called atonal music, including recordings of my father. Also, as discussed above in the context of the traditional orchestra repertoire, I arranged and composed pieces that allowed students to practice the experimental forms with which they had little or no experience. Eventually, as described in the experience above, we worked our way to entirely free improvisation. I believe my experiences and the experiences of my students confirm assertions by other scholars that providing opportunities for students to explore and experiment with creative materials in a structured, gradual process can lead to students being competent improvisors (Coss, 2019; Sawyer, 2011; Selby, 2022).

It occurs to me that my own learning of improvisation and free music had been largely unstructured. Again, as I described, my early musical experiences were mostly “sink or swim” situations that often led to less than stellar performances. The fact that I eventually became a successful improviser contributed to my sense that the authentic free music or jazz avant-garde experience necessitates being thrown into the proverbial water with the expectation that you will swim (i.e. just play). While that might work for some people, it also seems, based on my experiences at Hayes Memorial and the Rothbury School, that success is influenced by the use of methods that are aligned with individual capacity, culture and cultural expectations for performance. Thinking more about my own feelings of authenticity, I did not feel any less authentic when I engaged the students at the Rothbury School in a structured process to scaffold their success in free music. In fact, I ultimately had a sense that my authenticity as a jazz avant-garde artist had been validated.

I also believe that the Rothbury School culture contributed to my success. Luthans and Avolio assert that positive organizational contexts are important for authentic leadership success (Luthans & Avolio, 2003). The Rothbury School was a predominantly white, elite institution. I thought a lot about my own Black male identity in that place because it was discussed and emphasized among the community members. Diversity was an intentional topic of conversation, study and practice in the school, with an emphasis on racial and gender diversity. There were many conversations about race, the impacts of race, how people of all races should be accepted, how people from underprivileged backgrounds should be treated/helped. The school administrators were very intentional about leading the community in conversations about the responsibility of privilege with respect to equity and justice. I felt that I was valued as a Black male person at the Rothbury School. Even though I never brought every part of my Black identity (e.g. language, food, music, and other cultural performances) (Smitherman, 2021; Southern, 1997; Zafar, 2019) to school, I never felt as though I was being inauthentic as a Black male.

Transformational Religion

I suspect that because the Rothbury School is a religious school my religious background as shown on my resume, in some sense recommended me for the position. Among other things, leading chapel services was one of the main responsibilities of the position at the Rothbury School. In addition to my musical background, I had an undergraduate degree in religion from Andrews University, a Seventh-day Adventist institution. However, my Christian Seventh-day Adventist identity was not particularly emphasized at Hayes Memorial Adventist School. In fact, in my initial interview with the headmaster when we talked about Christianity and I said that I would do my best to help the students know Christ. I thought such an expression would make a positive impression. As a Seventh-day Adventist, I believed that “[e]vangelism, the very heart of Christianity, is the theme of primary importance to those called to herald God's last warning to a doomed world" (White, 2003). Immediately, the headmaster said, in so many words, that such a practice was not appropriate for the Rothbury School community – that I, as a faculty member, should not overtly evangelize.

The Christian part was more important than the Seventh-day Adventist part. In as much as the school was a Christian school, it felt important both to me and to the community that I identified as Christian. The strong background that I had in Bible study, mostly through my association with the Seventh-day Adventist church and education at Andrews, eventually served well in the Rothbury School. After three years at the school, I was invited to join the religion faculty. I attribute my ability to do well in religion teaching to the background I received in the Seventh-day Adventist church. The Rothbury School community believed in accepting and uplifting all people was a demonstration of their Christianity without overtly evangelizing. Even though I had not encountered such a perspective on Christianity in the Seventh-day Adventist church, it seemed well aligned with my personal values and perspective. For me, it was much more important that my music was spiritual and expressive of the love of God.

Turning back to the intersection of my Black male, Seventh-day Adventist, and jazz avant-garde identities,

I felt supported at that intersection at the Rothbury School. The school felt like the type of transformational organization described by Luthans and Avolio: “...organizations can also be characterized as exhibiting qualities of transformational leadership…transparent, energizing, intellectually stimulating, and supportive of developing leaders and followers to their full potential" (Luthans & Avolio, 2003, p. 256). The school leadership systematized both dialogue and action to “analyze social relations and the impact of class, power, and ideology on these, with the ultimate, if utopian, goal of freeing people from conditions that they themselves identify as being repressive" (Foster, 1989, p. 11). The Rothbury School engaged in community-wide conversation, readings, worship, curriculum development, service learning, and admissions that focused on equity and justice. Agosto and Roland (2018) connect these ideas of transformative leadership (see J. M. Burns, 1978) to intersectionality, the two frames, transformative leadership and intersectionality, can be mutually supportive.

I do not recall hearing the terms intersectionality or transformative leadership used at the Rothbury School. However, the leadership practices that were demonstrated, the activities – curricular and extracurricular – that were engaged by students, faculty and staff, and, ultimately, the feelings of worth and value that I experienced, suggest that those concepts were foundational to the operation of the school. I was able to be more of my authentic self as a Black male, Seventh-day Adventist, jazz avant-garde artist than I had in any other educational institution. Perhaps, most importantly, I was able to successfully lead students at the Rothbury School in joyful, liberating, God-given free musical experiences.